Extinction Along Interstate 10

The first time I saw the dinosaurs of Cabazon, looming like a kitschy desert mirage on the north side of Interstate 10, I was a young news reporter racing to cover the Liberace deathwatch in Palm Springs. Despite the urgency of my mission that day--grim reports leaking from behind the compound walls, tearful fans keeping vigil outside, a tabloid reporter already hauled away for attempted trespassing--I eased onto the freeway shoulder and spent a few minutes studying a creation that, to me, conveyed something profound and elemental about Southern California.

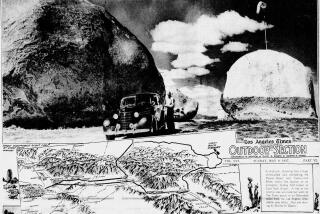

Back then, in 1987, the two dinosaurs rose nearly unobstructed from the desert floor. What struck me most was the clear sense of purpose that apparently had set them there in that desolate spot. Thereâs just nothing unintentional about 250 tons of steel-reinforced concrete fashioned into the shapes of a 150-foot-long apatosaurus (âDinneyâ) and a 65-foot-tall Tyrannosaurus rex (âRexâ). Someone had decided to build them, and in precisely that place, for some unfathomable reason.

For the record:

12:00 a.m. Nov. 30, 2005 For The Record

Los Angeles Times Wednesday November 30, 2005 Home Edition Main News Part A Page 2 National Desk 0 inches; 32 words Type of Material: Correction

Extinct animals -- Sundayâs Los Angeles Times Magazine article on Claude K. Bell, the creator of two dinosaur sculptures in Cabazon, referred to a mastodon as a dinosaur. It was a mammal.

For The Record

Los Angeles Times Sunday December 18, 2005 Home Edition Los Angeles Times Magazine Part I Page 6 Lat Magazine Desk 0 inches; 20 words Type of Material: Correction

The article âExtinction Along Interstate 10â (Nov. 27) incorrectly referred to a mastodon as a dinosaur. It was a mammal.

These things happen. The Watts Towers were no accident, and like the dinosaurs, they had no clear purpose, commercial or otherwise. Of course, everyone knows about Simon Rodia and his towers--the singular and profound result of one manâs obsession. But who built the dinosaurs? And why dinosaurs? And why way out in the middle of nowhere?

You already know how the Liberace story turned out. Legends arenât always built to last. But even as I made my way toward that unfolding desert drama, I couldnât shake the notion that, somewhere out there in that vast, arid weirdness, an even better story was just waiting to be told.

Claude K. Bell was 91 when I invited myself into his life. Iâd tracked him down through public records, then telephoned his wife, Anna, who at the time was a spry 71. Claude wasnât well, she explained, but if I came out to the desert, and Bell was feeling up to it, I might be able to talk to him for a little while.

I met him in his studio, just behind the dinosaurs, not far from the Wheel Inn restaurant. It was mid-summer, a dry inferno of a day, but the inside of Bellâs studio was dim and cool. He received me while sitting stiffly in his rocking chair. He was clearly frail. By then I already knew there were other problems. For years, Bell had welcomed visitors who wanted to see the viewing platform in Rexâs mouth--the one re-created for that famous scene in the film âPee-weeâs Big Adventureâ--and use the sliding board down his tail. Heâd also built a small gift shop in Dinneyâs belly. But on the day I met Bell, the whole operation was shut down. The hired caretaker had broken a hip, and Bellâs family was trying to decide what to do.

âI think we could go on if we found the right person, someone who understands,â Anna told me that day. âRight now weâre . . . trying to hang onto this for him, but we just canât get it together enough to do what he wanted to do.â

What Claude Bell wanted to do, essentially, was the same thing most of us want to do: make a permanent mark before leaving this world. But as he and his family told his story, Bellâs attempt to make his mark struck me as particularly poignant.

He grew up in Atlantic City, N.J., where he spent much of his youth creating sand sculptures for the loose change tourists would dig from their pockets. He got so good that for a while he made a career of it, touring the continent creating sand sculptures for fairs and exhibitions. During those years, Bell spent his time building things that had all the permanence of smoke. By dayâs end, his marvelous creations usually had been reduced to piles of nothing.

That Sisyphean sense of impermanence apparently wears on a man. âHe got tired of working on something for others, then seeing it torn down with no appreciation for its demise,â his wife told me. âHe said he was going to build something that nobody could tear down.â

Bell eventually found permanent employment as a sculptor at Knottâs Berry Farm, and he began raising his family in Buena Park. In 1945 he bought 60 acres of desert land, and it was there that he spent much of his free time. âI kept thinking, âWhy would anyone want to buy a piece of sand and dirt?â â Anna recalled. âI couldnât imagine what he was ever going to do with that piece of ground. But he never regretted it. Heâd come out here and look at it and say, âThatâs where Iâm going to build my dinosaur.â â

Interstate 10 was brand-new when the steel skeleton of Dinney began to take shape in the 1960s. By then Bell was in his mid-60s, and even older when he started work on Rex. He had a financial stake in the Wheel Inn, and he imagined his dinosaurs as a reliable magnet for passing motorists with an appetite. But making money was hardly Bellâs prime motivation. (He eventually spent about $300,000 and countless hours building the dinosaurs, but charged only 50 cents admission for adults, 25 cents for kids between 10 and 14, and nothing for kids under 10.) No, this clearly was about something else.

And so they rose, two dinosaurs marooned in that Godforsaken place. And there they have remained, silent testimony to their creatorâs pluck and to this land of infinite possibilities. Didnât most of us, after all, come here to build our dinosaurs?

At one point during my visit, Claude Bell leaned forward in his rocking chair and gestured toward a piece of plywood leaning against his studio wall. On it, he had sketched plans for a third dinosaur, a mastodon. âYouâve got to work from the inside out,â he said. âItâs kind of tricky getting around them.â He conceded that a mastodon âisnât in view at this time,â but even at 91, he wasnât entirely ruling it out.

Before I left that day, Anna flipped through a scrapbook of photographs of her husbandâs sculptures. âAll these things you see here were torn down,â she said. âThereâs only a few things left.â

The biggest of those stood just outside--massive, unmovable, as permanent as one man could make them. Bellâs partner in the Wheel Inn, who had helped assemble Dinneyâs steel skeleton, predicted that the dinos would be structurally sound for at least 500 years, and at one point Anna bragged that âtheyâd need a bulldozer and then something to get them down.â

I remember wanting to congratulate their creator for actually doing what so many of us want to do, for leaving a mark. But by then Claude Bell was asleep in his chair. And six weeks later, the man who built the Cabazon dinosaurs was dead.

Hereâs the thing about Southern California: Permanence is illusion. Legends wither. The past impedes the future. And so, sad to say, Claude Bellâs mighty dinosaurs have practically disappeared in the nearly two decades since they first caught my eye.

Oh, theyâre still there, standing strong and proud as ever on the same patch of desert. But Bellâs family eventually sold the 60 acres and the dinosaurs to an Orange County developer who wanted to make a mark of his own. In conjunction with a Christian group, the developer decided to use the dinosaurs as massive roadside billboards to help sell the biblical notion that life on Earth was a divine creation during Godâs one productive week rather than the result of millions of years of evolution. Bellâs dinosaurs have found gainful employment as proselytizers.

But at the same time, the dinosaurs have fallen into a modern version of a tar pit. First came a two-story Burger King, which rose between the dinosaurs and the interstate and partially blocked them from passing motorists. Another restaurant went up, as did a gas station. The dinosaurs seemed to get smaller, sinking deeper and deeper into a creeping commercial swamp that Bell never envisioned. The most thrilling way to see them these days is in satellite photographs. The last time I drove past, I was so distracted by the traffic around the nearby outlet malls and the new 27-story casino resort that rises into the desert sky like a Kubrick monolith, I didnât even notice the concrete creatures that once so fascinated and inspired me.

The moment struck me later as both sad and inevitable. Anyone with a dream can make their mark here. Few marks, though, are big enough to endure.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.