Next step for HIV vaccine

The search for an effective AIDS vaccine has been frustrating. Although a vaccine is considered the best hope of controlling the epidemic -- especially in poor countries where drugs are too costly -- more than 30 candidates have failed to halt infection.

Still, hope lingers. Many scientists are betting on an innovative vaccine that uses synthetic genes to rally the immune system in a new way. It has the potential, they say, to stop the spread of HIV, the virus that causes AIDS. Nearly 40 million people are infected with the virus.

âThis is the most promising approach in a long time, and the vaccine has prompted the most robust immune response that weâve seen against the AIDS virus,â says Dr. Judith Wasserheit, director of the international HIV Vaccine Trials Network, which is based in Seattle.

Because HIV constantly mutates, devising one vaccine to thwart different viral strains has proved challenging, and it hasnât been possible to use a weakened version of the virus -- as in vaccines for polio, smallpox or the flu. Such vaccines prompt immune responses, but HIV is too dangerous to be used as a preventive.

âWe couldnât use a weakened virus because the risks of infection were too great,â says Dr. Susan Buchbinder, director of HIV research for the San Francisco Department of Public Health who is involved in tests of the new vaccine.

Previous AIDS vaccines used synthetic copies of proteins found on the virusâ surface, in hopes of tricking the immune system to produce cells that would kill the virus. But in human tests, these vaccines didnât elicit a strong immune reaction or confer protection against all viral strains.

âHIV is a moving target, and no two surface proteins are alike, even within one individual,â Wasserheit says.

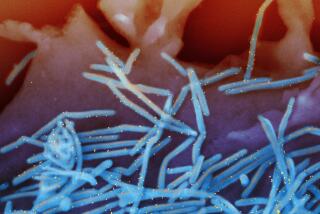

In contrast, the new vaccine, which is made by Merck & Co., is composed of three synthetic genes, called gag, pol and nef, that are found in the virusâ core and are believed to be critical for reproduction. The genes are inserted inside a gutted version of the cold-causing adenovirus, which serves as a microscopic cargo ship that ferries the genetic material inside the body. Because these genes donât change form even when HIV mutates, scientists think this type of vaccine may provide more universal protection against the different HIV strains.

In tests of the vaccine, it has elicited a novel immune response, known as cellular immunity, that triggers the production of T-cells. The body programs these cells to hunt down HIV-infected cells.

âThis is a totally new direction in vaccines, and the technology is much more sophisticated and powerful,â says John Shiver, head of the team at Merck Research Laboratories in West Point, Pa., that developed this new vaccine.

Animal and early human tests yielded encouraging results. In a 2002 study on monkeys who were purposely infected with HIV, the vaccine kept the virus at bay and prevented the animals from progressing to full blown AIDS. âThey remained healthy, and the virus was brought down to undetectable levels,â Shiver says.

And in a test involving 250 human volunteers who were given three injections over six months, 60% to 70% of the participants mounted an immune response against the HIV genes, which is equivalent to vaccines for other diseases such as the flu. The response endured over two years.

A larger clinical trial, which will eventually encompass 1,500 participants at high risk for contracting HIV in North America, South America, the Caribbean and Australia, was launched earlier this year to determine if the vaccine could block HIV infections, or reduce the amount of HIV in those who are infected, or both. Results should be available by 2010, but even if all goes well, the vaccine will have to undergo more human tests before it can be used by the public.

Still, âthis is an important step toward developing an effective vaccine,â Wasserheit says. âThis is a smart virus and hopefully weâll do better this time around.â

*

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX)

Other developments

Other AIDS vaccines are also being tested in humans, though they are not as far along as the Merck vaccine.

Chiron Corp., in Emeryville, Calif., is in the midst of clinical trials of a two-step vaccine regimen that will eventually involve about 168 participants in the U.S. The primary vaccine consists of HIV genes and is designed to provoke a cellular immune response; the booster vaccine consists of an HIV surface protein to elicit an antibody response.

In Thailand, the U.S. Department of Defense is conducting human trials of a combination HIV vaccine that takes a similar approach: One part of the vaccine is devised by the French vaccine maker, Sanofi-Aventis, to stimulate cellular immunity; the other part which is made by VaxGen Inc. of Brisbane, Calif., uses a surface protein to trigger antibody production.