The war’s over, but not for these brazen snipers

- Share via

Our troops are embattled in Iraq, and every day that conflict seems to get uglier. We are in the midst of a global war on terrorism whose front lines can be anywhere and which appears to have no end. And the goal of security for Americans in their homes is far away and not certain.

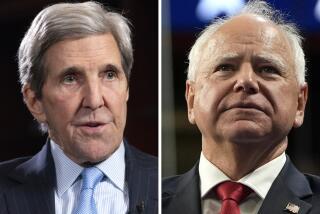

In the midst of all this, a Texas lawyer, John O’Neill, decides to refight the Vietnam War, which ended nearly 30 years ago, and by taking on Kerry’s proud claims of heroic service, attempts to make them the defining issue of the 2004 presidential election.

That is the sum of, and the total context for, “Unfit for Command,” a pamphlet of a book by O’Neill and Jerome R. Corsi, a veteran anti-communist crusader, attacking Sen. John Kerry’s credentials as a Vietnam War hero and candidate for commander-in-chief.

Pamphleteering goes back to the beginnings of American journalism, as early as the 18th century, and its tradition of strong advocacy continued into the 20th. Sometimes, these tracts were written by politicians or journalists crusading for reform; often, however, they were bitterly partisan attacks in which no charge was too base, no logic too frayed. Imagine CNN’s “Crossfire” without ground rules or an unrestrained Rush Limbaugh.

This book is not journalism. The authors feel no need to be factual, accurate, truthful, fair or, finally, compassionate, all of which we tell journalism students they should be. It’s more like pro wrestling -- a dirty hold, an eye gouge, a knee to the groin are all good, for they will draw cheers from the fans.

Yet, with its place high on the national bestsellers list, “Unfit for Command” has served an important purpose -- getting the country to discuss issues of character in the presidential campaign. For that matter, we have benefited from a dozen such books on both the left and the right whose authors argue their cases with a passion that had disappeared from politics.

And O’Neill has an angry passion. An Annapolis graduate who followed Kerry on the now-famous Swift boats of the Vietnam War, O’Neill writes as a lawyer compiling a brief, and his and Corsi’s argument is relentless:

Kerry cannot be trusted as president and commander-in-chief because, the authors write, he lied in Vietnam about his boats’ combat operations, he lied about his wounds, he lied to get medals, he lied to get out of Vietnam and he has continued lying about Vietnam for the last 35 years. He also lied when he asserted American soldiers had committed war crimes, and he gave aid and comfort to the Vietnamese Communists by joining a peace delegation -- and he has lied about that too.

In O’Neill and Corsi’s appraisal, Kerry has no integrity, and in an election that, as always, is as much about character as other issues, he deserves an ignominious defeat in the election on Tuesday.

Their case rests chiefly on the recollections of U.S. Navy veterans who served on the river patrols with and after Kerry. These 35-year-old memories are largely untested and often unattributed. O’Neill and Corsi do not use contemporaneous records, such as after-action reports or official histories, to support their case. And they did not go to Vietnam for any reporting.

But they do capitalize on Kerry’s apparent inventions -- his now-discarded 1968 “Christmas in Cambodia” story -- and on mistakes in the various Kerry biographies to assert, again and again, that Kerry lies.

All this leads nowhere, however, for their repeated misrepresentation of facts simply to build a case in the end undermines that case. Kerry’s enlistment in the U.S. Naval Reserve is portrayed as somehow cowardly, when in fact that is how the Navy recruited college students for its officer corps in the 1960s. Kerry’s assignment to the Navy’s riverine force was requested -- duty that some young officers sought in order to see combat -- and it was far from safe. His meetings in Paris with representatives of North Vietnam and the Viet Cong were no different from those that scores of other political and civic leaders had as Americans sought a way out of the quagmire. They were hardly treasonous.

There are also numerous little errors in “Unfit for Command” that suggest that facts were not a priority for the authors. The Ca Mau peninsula, for example, is the correct name of that Viet Cong stronghold in southern Vietnam that the U.S. Navy never fully penetrated. Fatah is not a “fringe group” of terrorists within the Palestine Liberation Organization but the political mainstay of Yasser Arafat.

The book fails to provide needed historical context for Kerry’s war -- the Communist mini-Tet offensive in February 1969, the turning of Lyndon Johnson’s war into Richard Nixon’s war after the 1968 presidential election, the change in strategies at the Pentagon and the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam in Saigon.

In the end, the great flaw in the O’Neill-Corsi argument is that it is not factual in important respects. Take its charge that Kerry shot a fleeing, though possibly armed, Vietnamese youth in the back and then was awarded the Silver Star for bravery under fire when there was no hostile fire. Doing what the authors failed to do, ABC News used military records to locate the village and sent a reporter to interview men and women there about their memories of that day.

The ABC program “Nightline” was then able this month to report that, yes, there was heavy fighting that day, that Viet Cong guerrillas were involved and that some were killed by the Americans. Indeed, the Viet Cong soldier apparently killed by Kerry is well remembered.

Questioned by “Nightline” host Ted Koppel, O’Neill held to his view, asserting that the Vietnamese villagers could not be believed because they live in a Communist society.

The greatest failure of this book is its motivation. It is an effort to rewrite history, to win a war that O’Neill and Corsi believe should not have been lost and to blame its opponents and critics for that defeat. The Vietnam War is over, and has been for more than three decades, yet it is the only real frame of reference for this book. The country has moved on, but O’Neill and Corsi have not. *

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.