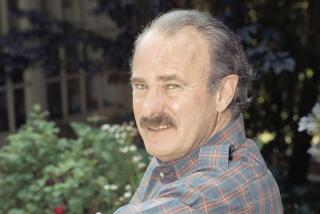

Cy Coleman, 75; Tony-Winning Composer Also Wrote Pop Hits

Cy Coleman, the Tony Award-winning composer of such Broadway shows as “Sweet Charity,” “On the Twentieth Century” and “City of Angels,” who also wrote some of the most enduring songs in pop music, including “Witchcraft” and “The Best Is Yet to Come,” died Thursday night. He was 75.

Coleman and his wife, Shelby, had attended the opening-night performance on Broadway of the Michael Frayn play “Democracy” and were at a party after the performance when Coleman said he was feeling ill. He went to New York Hospital, where he collapsed and died of heart failure, according to John Barlow, his publicist.

For the record:

12:00 a.m. Nov. 25, 2004 For The Record

Los Angeles Times Thursday November 25, 2004 Home Edition Main News Part A Page 2 National Desk 1 inches; 68 words Type of Material: Correction

New York high school -- Both the obituary for composer Cy Coleman that ran in Saturday’s California section and the appreciation article in Monday’s Calendar section said he had attended the High School of Music and the Arts in New York. The school’s correct name then was High School of Music & Art. Since 1961 it has been called High School of Music & Art and Performing Arts.

His death brought an outpouring of reaction from friends and colleagues.

“Cy was as fluent, if not more, in the language of music as he was in English,” songwriters Alan and Marilyn Bergman said in a statement.

“Never satisfied with what came so easily, Cy would probe and dig, and the result was music that was original, surprising and distinctively his.”

Writer Larry Gelbart, who collaborated with Coleman on the Broadway hit “City of Angels,” predicted that in the wake of Coleman’s death, “they’ll find any number of shows no one knew he was working on, like secret bank accounts. He was so prodigious. Music was his first language. If he ever had to stop writing, that would be the most stressful thing in his life.”

Lyricist Betty Comden, who along with her now-late partner, Adolph Green, collaborated with Coleman, said that “Cy was enthusiastic about music and a lot of fun.”

“His take on life was very funny, and he had a good sense of satire,” she said.

As Gelbart noted, Coleman was a prolific composer who always had a number of projects in the works. He premiered two new works within the last year -- “Like Jazz” at the Mark Taper Forum in Los Angeles and “The Great Ostrovsky,” a comedy about the American Yiddish theater, with book and lyrics by Avery Corman, at the Prince Music Theatre in Philadelphia.

“Like Jazz” examined the lives and spirits of jazz musicians in a series of musical portraits. Reed Johnson, writing in The Times, called it “a deft, sophisticated and tuneful tribute to jazz’s enduring influence over whatever it touches or brushes” and saluted Coleman’s “effortlessly urbane melodies.” The Bergmans wrote the lyrics, Gelbart the book, and Gordon Davidson directed. The creative team hopes that a Broadway version will open in the fall of 2005.

At the time of his death, Coleman was preparing to start rehearsals for an updated version, with new songs, of “Sweet Charity,” starring Christina Applegate. That production is scheduled to open on Broadway in April.

An excellent jazz pianist and performer, Coleman often used that genre as the underpinning of his work but could also include rhythms as diverse as country and western, funk and a Sousa-like march.

“If I have a song that becomes a hit, chances are I won’t go and write that song again,” he said some years ago. “A lot of people continue along the same style and milk it, and people will ask you to do that. Somehow that perversity in me remains, and I’ll go off to the other side of something else.”

“Like Jazz” director Davidson said that if he told Coleman, “We need to make a transition here,” he would sit down at the piano and make one.

“He might go off to refine it, but out of it would come something that didn’t exist before,” Davidson said. “He was open to a lot of different ways of looking at the same thing, which probably came from jazz.”

Coleman was born Seymour Kaufman in the Bronx on June 14, 1929. His parents owned the tenement building where the Kaufman family lived, and young Seymour took up the piano at the age of 4 after a tenant in the building moved and left one behind.

He quickly showed an aptitude for the instrument and began studying classical music. Between the ages of 6 and 9, he won several competitions and performed at Steinway Hall, Town Hall and Carnegie Hall. He gained much of his classical training at the High School of Music and the Arts and then the New York College of Music, from which he graduated in 1948. While in school, he earned money playing at weddings and bar mitzvahs.

At age 17, he wrote his first classical work, “Sonata in Seven Flats.” After switching his focus from classical music to jazz, he became the darling of the society-music scene in the late 1940s and early 1950s, playing at such swank Manhattan addresses as the Sherry Netherlands Hotel on Fifth Avenue. But soon he was playing in jazz clubs around town with the likes of Ella Fitzgerald and Illinois Jacquet, and, for a time, he ran his own jazz club, the Play Room.

His songwriting career also took off in the 1950s after he began a fruitful but often troubled collaboration with lyricist Carolyn Leigh. Between 1955 and 1962, the Coleman-Leigh team produced a number of songs that became American standards, including “Witchcraft,” a smash hit for Frank Sinatra in 1957, and “The Best Is Yet to Come,” first made famous by Mabel Mercer and then Sinatra.

Coleman’s songs also would be recorded by other great singers in American pop music, including Tony Bennett and Peggy Lee, who recorded entire albums of his music.

Though Coleman had contributed music to Broadway plays and musicals, his first full musical was with Leigh: the 1960 Lucille Ball vehicle “Wildcat,” which received lukewarm critical notices but included the tune “Hey Look Me Over,” which became a hit.

Coleman-Leigh’s next project was Neil Simon’s “Little Me” in 1962, which ran for 257 performances but produced no great hits. Although they worked together sporadically after that, it was effectively the end of a collaboration that had been marked by constant bickering.

After working on Hollywood films for a few years, Coleman returned to New York City and met Dorothy Fields, the lyricist whose credits include such standards as “I Can’t Give You Anything but Love,” “Sunny Side of the Street” and “The Way You Look Tonight.” Their first collaboration was the memorable “Sweet Charity,” which was adapted by Simon from a classic Fellini film and choreographed by Bob Fosse.

The production, which starred Gwen Verdon as a dance hall hostess looking for love, received generally lukewarm notices from critics. Writing in the New York Times, critic Stanley Kauffmann noted that the musical contained “no tunes that can be remembered.” The show ran for more than 600 performances and three of its numbers became big hits: “Big Spender,” “Baby, Dream Your Dreams” and “If My Friends Could See Me Now.”

The next Coleman-Fields collaboration, “Seesaw,” had a short run on Broadway.

Fields’ death in 1974 forced Coleman to find a new partner. He wrote “I Love My Wife,” which earned a Tony nomination and ran for two years, with Michael Stewart. And working with Comden and Green, he won his first Tony Award for “On the Twentieth Century,” an adaptation of the 1932 Ben Hecht-Charles MacArthur play. Despite mixed reviews, the production ran for well over a year and garnered six Tonys, including best score for a musical.

After that came the long-running hit “Barnum,” on the life of impresario P.T. Barnum, and the short-lived “Welcome to the Club.”

In 1989, Coleman used his jazz background to write “City of Angels,” for which he won his second best-score Tony. With a book by Gelbart and lyrics by David Zippel, “City of Angels” both satirizes and spoofs the film noir genre and hard-boiled detective fiction of the 1940s. Writing in Newsweek, critic Jack Kroll called it “smart, swingy, sexy and funny” and applauded Coleman’s score.

In 1991, Coleman, again collaborating with Comden and Green, won another best-score Tony for “The Will Rogers Follies,” which starred Keith Carradine as the fabled Oklahoma humorist.

His last Broadway show was the short-lived “The Life” in 1997.

Coleman worked in film as well, composing scores for a number of movies, including “Father Goose,” “The Art of Love,” “The Heartbreak Kid,” “Garbo Talks” and “Family Business.”

In addition to his Tony Awards, Coleman won three Emmys, two Grammys and an Oscar nomination for the film version of “Sweet Charity.”

For television, he conceived and co-wrote Shirley MacLaine’s 1974 special “If They Could See Me Now,” for which he won two of his Emmys, and produced her 1976 special “Gypsy in My Soul.”

Among his other honors were the ASCAP Foundation Richard Rodgers Award for Lifetime Achievement in the American Musical Theater. He served on the ASCAP board for many years.

On Nov. 6, the Actors’ Fund of America honored Coleman at Cal State L.A. The night was devoted to his music, performed by such stars as Chita Rivera, Lucie Arnaz and Tyne Daly.

“He was so alive and he was the last one to leave the party,” David Michaels, the fund’s West Coast development director, said Friday.

It is not generally known how Seymour Kaufman came to be Cy Coleman.

In an interview with a weekly Philadelphia newspaper earlier this year, Coleman said his first music publisher asked him to change his name.

“He convinced me that it was close enough and I wasn’t escaping Judaism,” Coleman told the Philadelphia Citypaper. “I called my mother. She said, ‘Seymour, do what makes you happy.’ ”

In addition to his wife, Coleman is survived by their 4-year-old daughter, Lily Cye, and two sisters, Yetta Colodne and Sylvia Birnbaum, both of New Jersey.

Times staff writer Don Shirley contributed to this report.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.