Guiding the growth of a wizard

- Share via

Daniel RADCLIFFE, or Harry Potter to you, isn’t talking about casting spells or Lord Voldemort. Instead, the 14-year-old is lusting after Cameron Diaz. “I could fly to Los Angeles and introduce myself,” Radcliffe says on the set of “Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban.” “I heard that she just broke up with her boyfriend.”

Harry and the students attending Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry were mere tots the last time we saw them. But now all have suddenly grown into teenagers, with all of the agitation that entails. And as the ages of the characters have multiplied so too have the adolescent preoccupations of the actors who play them.

When he’s not talking about his favorite “Charlie’s Angels” star, Radcliffe, starring as Harry for the third time, is going on about a special maneuver to swallow one’s own vomit while stuck in a car. A few moments later, it’s his favorite bands, which include Blur and the Darkness.

Rather than just idle banter, the offscreen “Harry Potter” conversations are really about what’s going on in “The Prisoner of Azkaban,” which, if you strip away its Quidditch games and Patronus charms, is what it’s like to become a teen.

Although Harry and classmates Ron Weasley (Rupert Grint) and Hermione Granger (Emma Watson) still must fight the forces of darkness, they also face an array of struggles common to any junior high student, including the search for self-confidence, acceptance and identity. Young wizards may be able to make broomsticks fly, but how do you make something of yourself?

The answers to that question help explain why Warner Bros. has handed off its billion-dollar family franchise to director Alfonso Cuaron, whose last film was the low-budget, sexually charged coming-of-age story “Y Tu Mama Tambien.”

Since “Y Tu Mama” related the passage from adolescence into adulthood, the studio and producer David Heyman reasoned that Cuaron was equally prepared to chronicle the transition from childhood into adolescence.

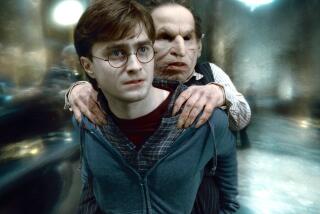

As Cuaron guides Radcliffe and Watson, 13, through a scene near the film’s conclusion, it’s impossible to ignore just how quickly the actors are growing up. They in fact are aging faster than the characters they depict, and their next film, 2005’s “Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire,” might be their last.

Radcliffe and Watson are not only taller but also handsome and beautiful, even under all the mud produced by a steady Scottish drizzle. “It’s wet and dirty and the kids are wet and dirty,” Cuaron says. “Don’t they look sexy?”

Rotating directors

Hollywood has a successful tradition of giving different directors a chance to reinterpret established movie titles. Fox selected Ridley Scott, James Cameron, David Fincher and Jean-Pierre Jeunet to make its “Alien” movies, and Paramount has enlisted Brian De Palma, John Woo and Joe Carnahan to direct its “Mission: Impossible” films.

Selecting Cuaron to take over “Harry Potter” seems both entirely reasonable and provocatively daring, especially for a studio that has played conservatively with the young wizard at every step. The stakes are arguably even higher with the third film, as it will be released amid the highly competitive summer (it opens June 4) rather than the shelter of November, when the first two movies debuted.

Out of caution, Warners nixed Rowling’s personal petition to hire “Brazil’s” Terry Gilliam to direct the first movie, 2001’s “Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone.” The studio instead picked “Home Alone’s” Chris Columbus, who also directed the first sequel, 2002’s “Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets.”

Both films were runaway global blockbusters, grossing more than $1.8 billion worldwide, yet critics said they lacked the creative audacity and spark that empower movies like Peter Jackson’s “The Lord of the Rings” series and that make Rowling’s books so memorable for kids and adults alike. The movies were hits, but they weren’t hip: They needed some PG-13, “Pirates of the Caribbean” pizazz.

Warners wasn’t trying to replace Columbus, but the director -- who first fantasized about making all seven movies (the number of books Rowling plans for the series) -- was ready for a change. He had lived in London for more than three years preparing, filming and editing his “Harry Potter” films, long enough that his American children were starting to speak with British accents. Columbus wanted to move back to Northern California and pursue other movie ideas.

The studio contemplated several options to fill his spot in the director’s chair: actor-director Kenneth Branagh, who played the self-important professor Gilderoy Lockhart in “The Chamber of Secrets”; Callie Khouri, who had just co-written and directed Warners’ “Divine Secrets of the Ya-Ya Sisterhood”; comedy director Ivan Reitman; and a 42-year-old from Mexico City whose last movie was so explicit that half the “Harry Potter” cast was too young to attend.

Warners knew Cuaron’s work quite well. Even though it admits to bungling the release, the studio had distributed Cuaron’s 1995 film, “A Little Princess,” an adaptation of Frances Burnett’s novel about a young girl who, not unlike Harry Potter, ends up in an unusual boarding school.

“That movie confirmed to me that he could live in the world of fantasy and children and not be treacly and also be a little bit dark,” says Alan Horn, president of Warner Bros. “And in ‘Y Tu Mama,’ he got such performances out of those two young boys. Now our protagonists in ‘Harry Potter’ are 13, entering puberty, and he understands that. The question was: Could he handle something of this size? It can be daunting.”

Horn wasn’t the only “Little Princess” fan. Rowling too had loved the film and even had ranked Cuaron just behind Gilliam among her preferences to direct the first film. Warners decided to take a chance and offered Cuaron the gig.

He didn’t immediately say yes. Thanks to “Y Tu Mama,” which was an art house hit nominated for an original screenplay Oscar, Cuaron was by his own admission Hollywood’s “flavor of the month” and was swimming in potential deals, including a shot to make a James Bond movie.

“I have to confess, I was a bit ignorant about the Harry Potter thing,” Cuaron says as a murder of trained crows swoops through the air, rehearsing for the director’s next shot. “Then they started to talk about it, and I was like, ‘Yeah, well ... I don’t know.’ Then someone said, ‘Please, look at the material, because I really want you to give an answer.’ So I read [screenwriter] Steve Kloves’ script. And it was great. And then I immediately read the book. And I was, frankly, amazed by the book and the script.”

Cuaron also saw there were significant advantages to directing a film in a series already underway. First, you inherit recognized characters and settings as well as actors familiar both with the roles and to the audience.

“Everything is established, so I don’t need to do exposition,” Cuaron says. “Chris crafted with [production designer] Stuart Craig a really eloquent universe. And Chris already established all the rules, so pretty much I don’t have to get into the matter of ‘OK, Hogwarts is this. And you’re a Muggle. And you’re a wizard.’

“By not having to do all this exposition, I can concentrate on character and the psychology of the characters.”

At the same time, Cuaron knew he was not at liberty to reimagine the film from the ground up. While he wasn’t exactly constrained to paint by the numbers, much of his filmmaking canvas already had been sketched in.

Even if he wanted to, for example, Cuaron couldn’t hire a new composer -- he was obligated to use John Williams, who provided the score for the first two “Harry Potter” films. Similarly, Cuaron couldn’t redesign Hogwarts, overhaul Diagon Alley, or recast any lead roles (outside of replacing Richard Harris, who played Hogwarts’ head of school, Albus Dumbledore, in the first two films but died in October 2002). And finally, Columbus would be looking over Cuaron’s shoulder, as he remained in London as one of the film’s executive producers.

“I wanted to make sure that the film didn’t stray too far from the world that the audience and the fans have sort of fallen in love with over the course of the first two movies,” Columbus says at the Leavesden studios on the outskirts of London, where many of the film’s sets were built and still reside. “It’s like putting nipples on the ‘Batman’ suit: It can get a little strange and a little weird to the audience.... If [the fans] have to adjust to too much change, they could have been turned off by the film.”

Before Cuaron made his decision on “The Prisoner of Azkaban,” he turned to his longtime filmmaking friend Guillermo del Toro for guidance.

“Guillermo had just finished directing ‘Blade 2,’ ” Cuaron says. “And he said, ‘Man, if you do it, I have only one piece of advice to give you: Don’t try to do an Alfonso Cuaron movie. Try to serve the franchise. And by serving the franchise, you may end up doing an Alfonso Cuaron movie.’ ”

Cuaron told Warners he would take the job.

The principals’ favorite

All of Rowling’s Harry Potter books have legions of admirers, and those aficionados can argue long into the night about which is the best novel, and why. The young actors who play Harry, Ron and Hermione are united in their appraisal of their favorite -- and it’s “The Prisoner of Azkaban.”

Their decision is certainly influenced by which book the threesome is filming and by the fact that at this point in production Rowling’s fifth book, the epic “Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix,” has yet to be published. Yet their “Prisoner of Azkaban” consensus is understandable and defensible. No less than Steven Spielberg has said the third book is the most cinematic of Rowling’s volumes.

If the first book introduced us to Harry’s peculiar life story and magical gifts, the second book was more of a “Hardy Boys” adventure. The third book, on the other hand, is distinguished by its psychological complexity. Harry’s misunderstood godfather, Sirius Black (Gary Oldman) and the avuncular Professor Remus Lupin (David Thewlis) become crucial characters in Harry’s development, while sinister villains called Dementors arrive. The book’s complex third act involves both time travel and Harry’s moving discovery of an inner strength he didn’t know he possessed.

In place of the good vs. evil clash pitting Harry against Lord Voldemort that is so prominent in the first two books, “The Prisoner of Azkaban” has at its center Harry’s struggling to understand his place in the world, grappling with his parents’ death, and trying to control his temper.

“Harry goes through a journey where he realizes that demons aren’t just things that go bump in the night but also can be painful emotions, worries about family, friends, the future, the monsters that lie within. And that’s a classic teenage issue,” Cuaron says as his special effects team tries to repair the film’s mechanized Buckbeak, a giant winged creature that has short-circuited in the rain.

“There’s a lot of teenage angst in this one, probably more than the book,” Radcliffe says by telephone a few weeks after filming is completed in December. “It’s much more of an internal journey for the children, especially for Harry. And he’s much more comfortable with confrontation, especially with [Professor Severus] Snape. He’s a lot angrier. If you had all this stuff happening to you in real life, you’d be pretty angry too.”

It’s not just Harry who’s acting out. “Hermione’s becoming a rebel,” Watson says. “She’s had enough of being pushed around and she’s not going to take it anymore. There’s a lot more girl power in the film.”

A ‘distinct piece of work’

Will you recognize “The Prisoner of Azkaban” as a movie from the same director who made “Y Tu Mama,” “Great Expectations” and “A Little Princess”? Probably so, but you might have to look closely, down to the modern trainers on Harry’s feet and the FCUK jeans on his legs.

“I think the audience will see it as a relative of the first two but as a very distinct piece of work,” producer Heyman says. The film could very well be rated PG-13, unlike its PG-rated predecessors. Both in production design and emotional reality, Cuaron is endeavoring to make his “Harry Potter” as contemporary as possible. To begin with, Ron, Hermione and Harry wear modern clothes. Columbus earlier had tried to make the students look like they shopped at Abercrombie & Fitch, but it didn’t work, so he dressed them in timeless school uniforms instead.

“Jo Rowling had always intended the characters to be wearing contemporary clothes under the cloaks,” Columbus says. “When we first tried that on the first film, it looked like a bad Halloween costume, like they were going trick-or-treating. Alfonso wanted to try something else. It will be interesting. It certainly was Jo’s original intent, so he’s being a little bit more faithful than I was.”

Cuaron’s world isn’t simply more modern. Treats in the film’s candy shop Honeydukes now include Day of the Dead sugar skulls.

“He’s very interested in eccentric detail,” production designer Craig says. “Hagrid’s hut, for example, is now peopled with 100 strange animals. Some of them are magical and bizarre, and some of them are bats and lizards. So Alfonso has taken on what already existed and was well established and it’s been embellished with these extra riches of detail. The Leaky Cauldron in the first two movies looked like a period movie; it was a very antiquated and a bit Dickensian. Now there is a range of characters there, in more contemporary clothes, and there’s a dart board.”

More so than in the previous two films, Cuaron will endeavor to explain the geography of Hogwarts and its surroundings. There will be long tracking shots as Harry and his classmates move from the Great Hall to their common rooms. Part of the motivation for traveling to Scotland, in fact, was to better establish the physical world in which Harry lives.

Ultimately, though, what will distinguish this movie is whether Cuaron succeeds in crafting a personal story that is as complicated as Veritaserum Truth Potion.

Cuaron, father to both a 20-year-old son and newborn daughter, clearly enjoys a special rapport with his young cast. “Wait a minute, Daniel,” he says, interrupting Radcliffe’s extended story about vomit. “The whole point of throwing up is to get it out of your stomach, not back in.”

“It got out eventually,” Radcliffe says. “I just had to swallow it at the time.” Cuaron then turns serious and gently counsels Radcliffe and Watson about how they might improve their performances in the film’s critical time-traveling conclusion.

“He reminds me of a kid, his enthusiasm, his mannerisms, his energy,” says Michael Gambon, the veteran Irish stage actor who is replacing Harris as Dumbledore. “He’s always laughing around the set.”

Long shoot, mammoth budget

Even though he’s just taken several days off for a Christmas break, fatigue creeps into Cuaron’s voice on a telephone call from London.

On “Y Tu Mama,” Cuaron had just a few weeks and a mere $5 million to make the movie. For “The Prisoner of Azkaban,” his shooting schedule stretched over eight months and his budget swelled to $200 million.

“No matter how much money you have, you are always 20 percent short,” says Cuaron, who worked without his favorite cinematographer, Emmanuel Lubezki (“The Prisoner of Azkaban’s” director of photography is Michael Seresin, longtime collaborator of director Alan Parker). “You can be on a low-budget movie or a big-budget movie, but you always wish you had 20 percent more. There was a point where you just dream, do whatever you want to do. And working with Steve Kloves was about dreaming. And then there was the window of frustration, where you are told, ‘This is the budget, and you can’t do that.’ But it was always about figuring out which movie we wanted to do with these resources and trying to fit everything into what I must say is a very healthy budget.”

The production was without any major mishaps, if you don’t count the raging Scottish brush fire sparked by a stray piece of burning coal from the Hogwarts Express train.

“It has been insane, but it has been good,” Cuaron says. “These kinds of films are not so much about filmmaking. They are about endurance. They just go on forever. And you have to keep up the pace all the time. If you fall behind in editing, it affects all the other departments. It’s like a marathon. Sometimes you’re in a zone. But sometimes, all of your tendons ache.” The next installment, “Goblet of Fire,” will be directed by “Mona Lisa Smile” filmmaker Mike Newell.

“The whole goal of taking a franchise in a new direction is what keeps them alive,” Cuaron says. “Jo Rowling said to me, ‘Don’t be literal. Just be faithful to the spirit.’ You might have hits and misses. But it’s always going to be fresh.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.