WPAâs Folk Art Is Back in Public Eye

WASHINGTON â When President Franklin D. Rooseveltâs Works Progress Administration launched a project to illustrate American folk art, it ended up with 18,527 watercolors of quilts, weather vanes, old tavern signs and merry-go-round animals -- a vast art gallery in itself.

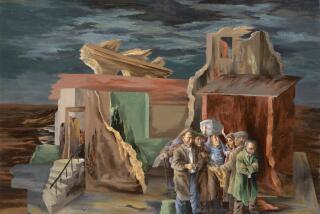

Now 80 of the artworks and 37 of the original objects are on display as the National Gallery of Art celebrates the 60th anniversary of its acquisition of that collection. The show, which opened Wednesday, is called âDrawing on Americaâs Past.â The artwork will be on view through March 2.

Visitors will learn about life-size sculptures that adorned shops in the 1800s. There were not only cigar-store Indians, but cigar-store Turks, a figure advertising lunch who may have been Mike âKingâ Kelly, a baseball star of the 1880s, and a comic carving of Captain Jinks of the Horse Marines, known from a Civil War song for feeding his horse corn and beans.

The gallery stores these thousands of paintings -- known as the âIndex of American Designâ -- in 829 boxes made of acid-free materials. It keeps them at ground level so they can be moved quickly in case of a flood. Light, temperature and humidity are carefully controlled.

While the paintings are well protected, the same cannot be said of the original folk art objects.

âWhen I was looking for original pieces to put with the paintings, I could only find a third to a half of them,â said Virginia Tuttle Clayton, the showâs curator.

What became of the rest isnât known, though some simply were destroyed by neglect.

âPeople left cigar-store Indians out in the rain, and I saw one carousel horse that children had played on so much that it was painted black and eventually collapsed,â Clayton said.

The paintings were part of Rooseveltâs efforts to pull the nation out of the Great Depression through public works projects. About 1,000 artists in 34 states and the District of Columbia took part. Top pay in New York was $23.50 a week, equivalent to about $250 today. That was barely enough to keep a small family alive, but more satisfying to an artist than selling apples on a street corner.

The project ended in 1942. World War II was raging and the job shortage was over. The final cost, Clayton estimates, was less than $100 per watercolor. The gallery won in a squabble between poet Archibald MacLeish, who was librarian of Congress, and Harry Hopkins, the WPA chief, over where the collection would be housed. The WPA art director, Holger Cahill, favored the gallery.

The main purpose of the index, Clayton said, was to provide American artists with a âusable pastâ that could inspire distinctive work in the way that history, mythology and Bible stories had inspired great European art. It didnât work out as expected, she writes in the exhibit catalog.

In the second half of the 20th century, the most famous American artists cultivated abstract art, which did not represent American history, folk art or anything else that most ordinary people could recognize -- just the artistâs thought and feeling. Painters such as Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko and Willem de Kooning dealt in lines, colors and shapes.

Harold Rosenberg, a critic who promoted the abstract painters, said their work and folk art were both expressions of âcoonskinism,â a word coined to recall the raccoon skin caps favored by Daniel Boone and other American pioneers. Europeans and Europeanized Americans of the 1800s preferred hats made of beaver skin.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

Weâll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.