POETS’ CORNER

THE COMPLETE POETRY OF CATULLUS

Translated from the Latin by David Mulroy

University of Wisconsin Press: 170 pp., $15.95 paper

The voice of the ancient Roman poet, Catullus, like Sappho’s, sounds contemporary. This new translation by David Mulroy is almost too contemporary. A back-jacket quote sets Catullus up as “a wild young poet in Julius Caesar’s Rome.” His life, we are told, “was akin to pulp fiction.” Beyond this hyperbolic swagger (like Catullus on steroids), there’s certainly truth to the claims of anarchical behavior.

Catullus was a cocky, brilliant wiseguy who had affairs with married women (including wives of government officials) and wrote freely about his dalliances. He was not above insulting pompous political types (what a fresh breeze!), making sport of Caesar himself. He mocked the back-alley buggery and sexual conquests of his friends. But he also had a complex, powerful lyric sense, a sadness and a grandeur. The woman he loved (and whom he addresses in a deferential, sometimes disturbing manner) was his “Lesbia” (probably a woman named Clodia Mettelli, a forceful and extremely notorious individual).

Mulroy’s “notes” and contextualization of the work are persuasive, tonic and conscientious, but his translations suffer. A famous poem of Catullus to Lesbia about the death of her pet sparrow is a literal, clunky translation, making light of the bird’s death when, in fact, the poem’s subject is grief itself and the provocative relationship between Catullus and his lover. Other translators (like Peter Whigham, for example) have rendered the poem in staccato flashes, beginning with “Who loves beauty / veil her statues... “ Compare this to “Commence lamentation, Venuses, Cupids... “ in Mulroy’s opening. Granted, this particular translation-cum-notes seems directed to students of Latin--but scholar-initiates, like young poets, can only benefit from understanding the complexities of the attitudes and language of a poet read and deeply admired a thousand years after his death.

*

V:WAVESON.NETS / LOSING L’UNA

By Stephanie Strickland

Penguin: 128 pp., $18 paper

The hypertext poet Stephanie Strickland has a new book of poems that is “invertible,” thus providing two “beginnings” (and two completely different covers) to the collection. Here is the publisher’s description: “At the book’s opened center, where ‘Losing L’Una’ turns over into ‘WaveSon.nets’ and vice-versa, there will be a pointer (www.Vniverse.com) to the book’s third section, which will go up on the Web when the book comes out.”

For the unexceptional poet, the term “hypertext” can be a synonym for self-indulgent composition, no editing and (in a certain type of discourse) a naif’s appropriation of the “languages” of science and math--as if the acquisition of technical vocabularies and concepts were a simple matter of Bachelardian poetic “reverie.” Not so in Strickland’s case. This book reminds me a little of Susan Wheeler’s “Source Codes,” a book whose “experiments” also include a pastiche of “high” and “low” diction, text disruption and the play of external analogs. Strickland, like Wheeler, has a sassy, funny mimic’s sense--but also a steely sense of grammar and structure--traditional forms are included, inverted, abstracted, sent up--but attended to.

In “V:WaveSon.nets/Losing L’Una” (either book), there are sonnet, haiku and aphoristic echoes. Strickland’s “muse,” Simone Weil, is invoked throughout and the elegiac feel of these poems is haunting and passionate, inspiring the reader to listen to the “waveforms” of the human voice. They read like the one long episodic dream of a being who exists between atmospheres, like a mermaid: From “WaveSon.nets 2”: “If you understand red, you understand ruby, / you understand light bubbling up struck seam / first morning cliff; you do not / mock the real / as you watch it subside and divide and then run / like morning into the virtual.”

*

SELECTED POEMS

By Mona Van Duyn

Alfred A. Knopf: 224 pp., $27.50

Mona Van Duyn’s four decades of poems unfold here in impressive array--managing to be both accessible and profound. Her first book, “Valentines to the Wide World,” was published in 1959, announcing the arrival of a poet-virtuoso, whose preferred style leaned to the modest but mildly coercive: “Beauty is merciless and intemperate. / Who, turning this way and that, by day, by night, / still stands in the heart-felt storm of its benefit ... / ... And never will temper it, / but against that rage slowly may learn to pit / love and art, which are compassionate.”

From this to the minimalist sonnets of “Firefall,” her latest book--”Line fourteen / Closes / to serene / supposes.” --is a continent of metaphysical, formal eloquence. The reader entering this body of distinguished work will not be disappointed. The oeuvre of this former U.S. poet laureate generates, even in its ironic moments, joy.

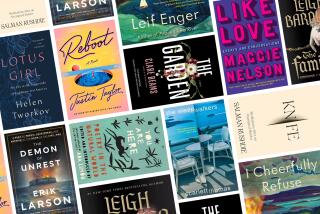

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.