Following in His Footnotes

- Share via

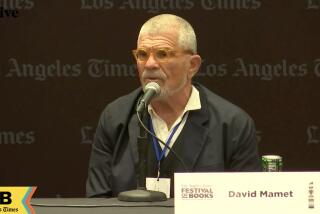

It was Alfred North Whitehead who said “all philosophy is merely footnotes to Plato.” But it has taken David Mamet to write a footnote positing Aristotle as the true author of “Dink Stover at Yale.” This observation is only one of the many instances of serendipity in Mamet’s latest work of fiction, a curio titled “Wilson: A Consideration of the Sources.”

Presumably written several hundred years from now, “Wilson” is a super-academic commentary on the ur-historical text of future historians--the memories of a woman named Ginger who may have been the wife of President Woodrow Wilson or a later President Wilson.

Ginger’s memories, preserved on hard drive, are all that remain of the recorded history of man well into the 21st century, following a computer crash of catastrophic proportions (caused by the Cola Riots or the fire at the Stop ‘n’ Shop). Yet all is not lost. Academics have survived with the hermeneutic hardiness of cockroaches. Out of Ginger’s fragments they shore themselves with commentary upon commentary.

What that means is that “Wilson” is 100% narrative-free. More than 300 pages of analysis, some as densely covered with footnotes and footnotes to footnotes to footnotes as a PhD thesis on “The Sound and the Fury.”

Fortunately, in many ways, the analysis owes more to Mel Brooks than Cleanth Brooks. Take a chapter title, please: “Birnam Wood Do Come to Dunsinane or: Cheezit, the Copse.” Or an epigram or two: “We now proceed from the confusing to the arbitrary,” attributed to Epictetus in “Who’s Minding the Stoa?” or “‘For how can we comprehend the whole without an understanding of the parks?’ Olmstead.”

Even in the footnotes, high culture and low culture rub diphthongs--”And besides, the wench is dead” (Christopher Marlowe) becomes “And besides, the witch is dead” (Yip Harburg). A passing knowledge of Cockney rhyming slang helps explain why “Memories of the Berkshire Hunt” may have more to do with foxes than with sherry. For most readers, an undergraduate familiarity with National Lampoon is sufficient to enjoy the pokes and jabs that Mamet makes on ivy-encrusted nib-scratchers of academe.

When academics spin out tomes of hundreds of thousands of footnoted and indexed words on subjects whose dryness is matched only by their obscurity, the motive is clear: tenure. When Mamet, arguably the most successful playwright-filmmaker on the planet, does the same, however, the pursuit of tenure does not seem, on first blush, sufficient explanation. Why then this textual perversity?

There is a reasonable evolutionary argument to the descent of Mamet from the prolixity of Samuel Beckett and the economy of Harold Pinter. Yet Mamet--at least the playwriting, screenwriting Mamet--has always been a writer for whom words matter, and more than just mere words, the choice of the best words.

Reading “Wilson” is difficult because it is rarely clear why Mamet chose the words or the paragraphs he did. It seems as if every word, every paragraph, every sermon, diatribe, midrash, bad joke, good joke, doggerel, ditty, proverb, beatitude, headline and footnote that hadn’t made it into his classic “Glengarry Glen Ross” or “American Buffalo” or the film “Homicide” was unspooled by some latter-day Krapp (of Beckett’s “Krapp’s Last Tape” fame) whittling away at a hard drive with a pair of box cutters and then re-constructed by the Firesign Theatre. At best, the effect is as entertaining as a Grossingers double-bill featuring Joyce’s “Finnegan’s Wake” and Nabokov’s “Pale Fire” recited, say, by Shecky Green.

Yet by trying to figure out “Wilson,” are we falling prey to the same dangers as those who sought meaning behind the memories of Ginger? The academics who have searched for an “Inner Code,” suggests one “Wilson” commentator, have been suckers for a ploy “to market Whippies. And those obtuse enough to’ve ‘sent their boxtops in,’ found out the same.”

Another commentator provides, perhaps, the best clue to the existence of this curious project: “Unfortunately, it is not only religions which attract, inveigle and entrap by their claims to simplicity. We all are attracted to the undiscovered. In it we find that titillation of ‘something-for-nothing,’ whether in real estate, in exploration, science, engineering--the attraction of each and all may be reduced to that sympathetic excitation of the quintessential human survival mechanism: the ability to imagine a way of getting out of work.”

There you have it: the explanation for the existence of cockroaches, the novels of Anthony Trollope and the Hundred Years’ War. And perhaps those of us historically obtuse enough to have sent in our Mamet box tops are merely suckers. But there are worse ways than reading “Wilson” to get out of work.

*

Jonathan Levi is a contributing writer to Book Review.