A Gaggle of Quackery Going Mainstream

- Share via

MINNEAPOLIS — Feeling run-down? A bit saggy of spirit? Step right up to the Orgone Energy Accumulator. It looks like a coffin, but it’s filled with pure energy. Sit inside and soak up vigor.

Men, does your sex life need a boost? Give this prostate gland warmer a try. Women, desperate to expand your bust? Try these suction cups--in such a pretty shade of pink.

Or maybe you’re suffering from varicose veins? Arthritis? Kidney trouble? Spit on a piece of paper. Slip it into this box. Adjust the dials, and zap--it will send out healthful vibrations that will have you cured by breakfast.

All this and more was available until Jan. 27 at the Museum of Questionable Devices, a screwball collection that proved the maxim, “If it looks too good to be true, it is.” (And suggested a corollary: You can make a mint selling it just the same.)

Time to Go

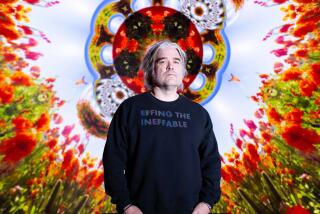

Museum founder Bob McCoy packed up his quackery hall of fame last week, saying it was time to retire (at age 75) after nearly two decades of devotion to the scam. But if you need a spin in the MacGregor Rejuvenator, fear not. McCoy has donated 325 of his best frauds to the Science Museum of Minnesota in St. Paul.

That means the magnetic Immortality Ring and the Crosley Xervac vacuum pump for hair growth soon will go on display in a museum of “serious” science.

And serious scientists are delighted.

For, while the bogus cures always are good for a chuckle (or a wince, in the case of the rectal dilators), the collection has a sober message as well: Be skeptical. Question authority. Think.

It’s easy to make fun of a machine that purported to cure most any illness by vibrating the air. But thousands fell for the Coetherator in the 1930s. In 1976, about 4 million women bought the foot-powered breast enlarger. And today, millions more are falling for other “treatments” every bit as worthless.

Just last month, an Iowa judge blocked sales of a machine touted to regenerate breast tissue. Oregon recently cracked down on claims that an “electro-dermal” device could detect food allergies by probing for imbalances in a patient’s “electromagnetic flow.” As for the Immortality Rings--”believed to stop aging permanently!!!”--they’re still on sale through the Internet, at $25 a pair.

“The fact is, [quack devices] are a really serious problem,” said Dr. Stephen Barrett, who crusades to expose such fraud through his Web site, https://www.quackwatch.com. “People fall for them all the time, and there’s very little protection.”

Or, as McCoy puts it: “You know that phrase, there’s a sucker born every minute? Well, there’s a crook born every hour to take advantage of those suckers.”

But it’s not money alone that’s at stake.

The most wrenching exhibit in McCoy’s collection may well be the Tricho Machine, circa 1925. The device used X-rays to remove “superfluous hair,” and young women flocked to beauty salons to try it. Many returned for dozens of treatments--only to suffer, in later years, from debilitating ulcers, receding gums and cancer.

Like many of the “miracle” machines in the collection, the Tricho played off a genuine medical advance: the discovery of X-rays. Consumers then, as now, knew that the latest scientific finds were being harnessed to improve health care. So they had little reason to question some of the outlandish claims made by quacks.

If an invisible X-ray could see through skin and diagnose internal injuries, why should they doubt that a “violet ray” treatment would eliminate freckles and redistribute fat? Or that an “ozone generator” could cure a torn tendon with glass tubes that lit up neon-bright?

When transistor radios were all the rage, AM radio waves were touted as a marvelous cure. When radium was discovered, quacks invented radioactive aphrodisiacs and gamma ray fountains of youth. When aerobic exercise took off in the 1980s, out came “aerobic eye exercise glasses” to improve vision.

A Wacky History

“The whole history of science is embodied in these wacky devices,” said Anne Hornickel, an executive at the Science Museum of Minnesota. “They tell an amazing story.”

Hornickel and her colleagues are working on how to integrate that story into the Science Museum. In some cases, McCoy’s devices will take their place alongside existing displays.

The human body exhibit, for instance, may host McCoy’s foot X-ray machine, used in shoe stores in the 1950s to guarantee a perfect fit. And the gallery that deals with light waves will be a natural for the Specto-Chrome, a box that flashed colored lights on a nude patient to “cure” 200 diseases, including bubonic plague and anthrax. (The machine--little more than color filters and a light bulb--earned its inventor more than $1 million in the 1930s.)

Other devices might become interactive exhibits. Visitors might test the vibrating bed, designed to straighten curved spines. And McCoy already has taught museum staff members how to operate the antique “psychograph,” a contraption that looks like a cross between a postmodern chandelier and a medieval torture device. The machine deduces a patient’s personality from reading the bumps on the head, then suggests suitable careers, from actor to zeppelin attendant.

Quackery Connoisseur

The psychograph was one of McCoy’s first questionable devices; a friend gave it to him in the 1970s. Always interested in uncovering deceptions (he founded the Minnesota Skeptics Assn. to do just that), McCoy soon became a connoisseur of quackery.

He found some devices at estate sales. Others were sent by strangers as word of his curious collection spread. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the American Medical Assn. each scoured their warehouses for sham devices to lend McCoy. Medical historians also provided thousands of documents, from breathless advertisements to newspaper exposes to government posters warning that certain devices could be dangerous. (McCoy has collected them all in a recent book called “Quack! Tales of Medical Fraud From the Museum of Questionable Medical Devices.”)

However the Science Museum uses the collection, McCoy’s supporters hope it will be appreciated as more than just a gag.

“People want to believe in technology. They want to have trust in health-care professionals,” said Dr. Robert S. Baratz, president of the private National Council Against Health Fraud. “The value of this type of museum is to point out that sometimes these things are frauds.”