Springing âCrouching Tigerâ on U.S. Audiences

The buzz began the first time it hit the big screen. Whether it was at Cannes, Berlin,Venice or Toronto, the epic martial arts romantic drama âCrouching Tiger, Hidden Dragonâ immediately began building momentum, hitting Hollywood like a typhoon.

Once it was released nationwide, it struck a chord with an unprecedented range of movie fans, from suburban teen skate-rats who had never seen a subtitled film, to hip-hop fans, to middle-aged art-house movie lovers. Somehow, this fantasy Mandarin-language movie set in 19th century China tapped into the soul of America. Though the story of noble Chinese warriors and a willful young girl who steals a magical sword was based on the ancient form of storytelling called Wuxia Pian, American audiences understood the filmâs humanity, adventure, unrequited love and tragedy.

For the record:

12:00 a.m. March 28, 2001 For the Record

Los Angeles Times Wednesday March 28, 2001 Home Edition Calendar Part F Page 2 Entertainment Desk 2 inches; 40 words Type of Material: Correction

Marketing campaign--The Academy Award marketing and publicity campaign for âCrouching Tiger, Hidden Dragonâ was handled entirely by Sony Pictures Classics, which released the film. A story about the movie in Mondayâs Calendar incorrectly credited the campaign to Sony Pictures.

Even the filmâs distributor, Sony Pictures Classics, was caught off guard by the pictureâs popularity. Never had any of its previously released films received such recognition and widespread appeal. Once the Oscar campaign began in earnest, the small specialty arm of Sony Pictures could count on its mother studio to back it. Indeed, Sony Pictures, having few othernominees, launched an intense publicity campaign pushing the film in the trades and television.

Their aggressive marketing and shrewd publicity paid off with the tidal wave crashing through the Academy Awards on Sunday night. The film swept into Hollywoodâs ultimate insider party, winning four awards, including best foreign film and cinematography.

The film has managed to straddle all worlds in the film industry. It was lavished with praise by critics. It received the admiration of the independent film world--winning three awards at the Independent Spirit Awards on Saturday--as well as the attention of the mainstream studio world.

It is probably safe to say no one in Hollywood has had as thrilling a year as the filmâs modest director, Ang Lee. The film he thought would be a sure-fire flop has actually made history: It has become the biggest-grossing foreign film of all time, making more than $100 million to date, shattering the former record set by the 1998 Italian movie âLife Is Beautiful,â which made $58 million. It garnered the most academy nominations of any foreign-language film ever (10). And it won Lee best director honors from the Directors Guild of America, making him the first to win that award for a foreign-language film.

All these awards and accolades are a vindication for Lee and producing partner/co-writer James Schamus.

The filmâs epic nature mirrored the odyssey of making it. It began with a difficult script--an adaptation of the fourth part of a five-part Chinese novel. Schamus and Lee patched together a story that was a little bit Western in sensibility and a little bit Asian in its foundation. Somehow, Schamus, Lee and the translator were able to combine layers of Chinese cultural nuances into an action-adventure romantic film that non-Chinese could relate to. After dozens of rewrites and translations back and forth from Mandarin to English, the script was finally completed.

But perhaps the hardest work came in raising the money to make the film. Schamus had to find $15 million from a quilt-work of financiers in Taiwan, the U.S. and Europe for a Chinese-language film--hardly a sure bet. Finally, after seven months of building financial bridges across three continents, Schamus had the financing secured.

But their agony did not stop there. Lee was bent on filming in mainland China, the first time a Taiwanese filmmaker has been allowed to do so since the Communist Revolution. They faced cold, rough weather. The stars got sick. They broke down emotionally. They were pummeled by one of the toughest martial arts choreographers around. Star Michelle Yeoh even suffered a broken knee.

But Lee had a vision that he would not compromise. Even if that meant arguing and in his soft-spoken manner convincing his veteran choreographer, Yuen Wo Ping (who also choreographed âThe Matrixâ), that his actors could indeed fly through the air and stage a sword fight on nimble-branched bamboo trees. His vision also included filming in nearly every corner of China--Beijing, the Gobi Desert, the Taklamakan Plateau, north of Tibet, to Urumchi bordered by Mongolia, then south to the bamboo forests in Anji--lugging crew and cast right alongside him.

But it must all seem like a long-ago dream. The sweet taste of success has cleaned Leeâs palate.

*

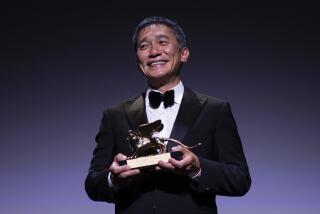

âI must thank the academy for giving me this award tonight. Itâs a great honor to me, to the people of Hong Kong and to Chinese people all over the world.â

PETER PAU, accepting the cinematography award for âCrouching Tiger, Hidden Dragonâ

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.