Sandinista Paper Returns, but Ex-Staffers Aren’t Impressed

MANAGUA, Nicaragua — It’s not sold on newsstands or even on the streets, but Barricada, the newspaper of the Sandinista National Liberation Front, is once again appearing in print after a hiatus of more than two years.

The newspaper’s closure in January 1998 marked a low point in the fortunes of the leftist-guerrillas-turned-politicians who overthrew the Somoza family dictatorship in 1979 and went on to govern Nicaragua as a socialist country for more than a decade.

It was an admission that not enough readers and advertisers cared about the Sandinista version of the news to sustain a daily paper. But with midterm elections coming up, the party has again found a need for a printed voice to complement its radio station, Radio Ya.

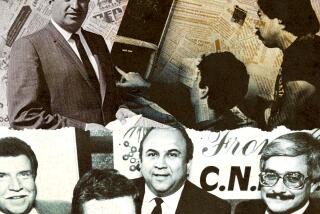

“We did not have a single newspaper,” said Tomas Borge, a former Sandinista comandante who became part-owner of the paper after he paid its debts by mortgaging one of his vacation homes. “We made the decision to start publishing Barricada again after a sinuous and difficult existence.”

But the publication’s reappearance has not been universally applauded.

“They are trying to revive a tradition, but they have done it quite badly,” said Carlos F. Chamorro, who was Barricada’s editor for 14 years. “This is not Barricada--it looks more like the Barricada of 1979 than a newspaper published in the year 2000.”

The first edition of Barricada rolled off the presses July 25, 1979, about a week after the Sandinista tanks rolled into Managua, the capital, and the last Somoza left, ending a four-decade-long dynasty. The writers were party activists--not professional journalists--who relied on the headlights of delivery trucks for enough light to put the newspaper together.

Like the revived edition, that first Barricada was thin and unabashedly Sandinista. Its logo was a rifleman standing behind a barricade, ready to shoot. That was later modified to the outline of a cowboy hat--the Sandinista symbol--and a Nicaraguan flag.

The biggest difference is that the new Barricada is weekly.

“A daily newspaper is a costly, complicated undertaking,” Borge said. “We do not have the economic conditions for that.”

In fact, he said, the newspaper is being printed at cost. Sandinistas holding elected office are being charged an unspecified fee to cover those costs because the newspaper has no advertising yet.

Distribution relies on party activists who buy 100 copies at 30 cents each and resell them to friends at cost. The volunteer editor and a managing editor paid by the party supervise three staff writers and a photographer.

Although the new version recalls that first issue, it looks nothing like the Barricada overseen by Chamorro, a member of Nicaragua’s best-known publishing family and son of former President Violeta Barrios de Chamorro. Under Chamorro, in 1993, the newspaper revealed the collaboration of members of the Salvadoran left, which had negotiated a peace treaty with the government just a year before, in creating a cache of arms and false passports that had been discovered in Managua.

That scoop infuriated the Sandinista leadership, which was embarrassed in front of its allies. “They were talking about freedom of expression and the right of journalistic independence,” Borge said. “Well, there are no independent newspapers.”

In 1994, Chamorro was fired and Borge took over as publisher. “They still had this tendency to independence,” he said. “I was never able to overcome that.”

Barricada had begun to lose circulation and advertising in 1990, when the Sandinistas lost the presidential election. The drop became sharper after Chamorro was fired, followed in the next week by about 80% of the staff.

Finally, only three professional journalists were left, recalled Juan Ramon Huerta, the daily Barricada’s last editor. “We thought we could do good journalism even though the party owned the paper,” he said. “We failed.”

With the remaining staff fighting the party leaders and the newspaper sinking deeper into debt, Borge closed Barricada--until the weekly began appearing two months ago.

What saddens Chamorro, Huerta and other former Barricada staffers most is recognizing that this is the kind of Barricada that the Sandinista leadership wanted all along.

“The history of Barricada reflects the inability of the Sandinista Front to adapt to the new era,” Chamorro said. “For them, the media is just an extension of the party.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.