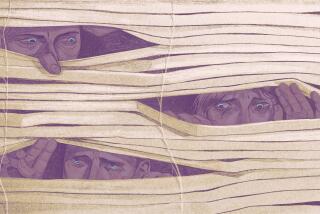

The ‘Big Brother’ Teens Don’t Need

- Share via

Jason Allami is no expert on teenagers, but worried parents call him at his Thousand Oaks spy shop all the time: We think our son is doing drugs, but we’re not sure. . . . We don’t know where our daughter goes at night. . . . We’re concerned about our kid’s new friends. . . .

Even in a day when the oddball child is viewed as a dangerous misfit and the dumb joke as a battle cry, these aren’t the calls Allami relishes. When parents want to plant a tiny video camera in Susie’s bedroom or buy an unobtrusive little recorder to monitor her calls, there’s something so profoundly wrong that Allami tries to ward them off.

“I tell them the answer isn’t in this stuff,” says Allami, gesturing to the scopes and screens on the shelves of his modest store’s back room. “ ‘Don’t spy on your kids,’ I tell them. ‘Spend time with your kids.’ ”

It’s not the most effective sales pitch for surveillance equipment, but Allami doesn’t care.

“I’m an engineer, I’m an idealist,” he insists. “I’m not a very good salesman.”

Allami plans to move SPI Communications to an industrial park one of these days. He’s in a shopping center now, cheek by jowl with a sushi bar, a credit union, a place that sells party hats. The walk-in traffic is getting to him.

A lot of people ask for concealed listening devices. “I have to tell them that we don’t have bugs, but also to not go around asking for them, because they’re illegal. They think it’s like a grocery store--instead of buying a quart of milk, you just go in and buy a bug.”

When he started SPI--also called the Over the Counter Spy Store--three years ago, Allami was a lot more eager for the retail trade. But by now he’s heard from too many jealous husbands and outraged wives, and even kids interested in innocent childlike pastimes, like wiretapping.

Besides, revenue from corporate business came to dwarf the occasional sale of items like the briefcase that administers a 50,000-volt shock and the framed etching of chickadees that you can swing open for easy access to your gun.

When companies come to Allami, it isn’t because they’re seeking to reward employee initiative.

“Their biggest single problem is employee dishonesty,” he said.

Maybe the truck drivers are racking up more mileage than usual. Solution: a tracking device about as big as a deck of cards, hidden under the seat or on the chassis.

Or maybe some supervisor thinks the data-entry people are sitting at their computers looking a little too rapt, too engaged. Solution: a program that not only lists the Web sites they visit, but keeps tabs on the e-mail they send and receive.

Sound chilling? I’d mention the words “Big Brother,” but, between you and me, I think someone might be listening.

“Let’s say you’re a restaurant owner who doesn’t want to spend all day there,” Allami said. “We have a system that allows you to dial in from home and see what’s happening in any corner of your business.”

If your bartender is taking a nip himself, a camera will catch him. Likewise for the cook smoking dope in the freezer and the waitress leaving two hours early. The cameras can be out in the open--an option Allami recommends--or they can be hidden in devices as innocuous as clocks and lighting fixtures. In any event, the panorama of betrayal is yours to behold on your personal computer, in the privacy, or so you think, of your own home.

Allami lives in a gated community with his wife and their two small children. He has a degree in electrical engineering and an MBA. When the frightened parents call, he tries to tell them they shouldn’t subject their children to the kind of high-tech monitoring they might be subjected to at work.

“You just have to spend the time,” he says.

When he did, he saw his daughter in a deep trance before a TV spewing the usual spew. That’s when he did the unthinkable. The family no longer has cable.

Allami acknowledged that he did place a camera--”the biggest one I could find”--in the middle of his house to check out a nanny who came to live with the family.

“After we watched her for a month, we realized she was trustworthy and took the camera away,” he said. “I didn’t want her to feel alienated.”

Steve Chawkins is a Times staff writer. His e-mail address is [email protected].