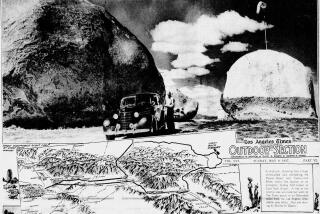

AUSTRALIA’S ROCK STAR

ULURU-KATA TJUTA NATIONAL PARK, Australia — Away in the outback, north of Nurrari Lakes and south of the Tanami Desert, lies a big red stone that some people call Uluru and others call Ayers Rock. Occasionally you catch a kangaroo waiting in its shade. At dusk the dingos sing, and tourist-bearing camels plod through the bush, single file.

And each day, facing this marvel shortly after dawn, hundreds of travelers find their inner Edmund Hillarys yearning to be freed. Soon the travelers are creeping up the steep, slick, mile-long trail to the top. For the first 600 yards, where the incline is steepest, they grip a steel chain and posts that were placed in the 1960s. Nearer the top, they trudge along a wriggling dotted white line while the wind howls and the sun climbs above in a very blue sky.

Many scientists believe that this single chunk of sandstone is the largest monolith on the planet, that it extends as much as three miles beneath the earth’s surface, an iceberg of the desert.

A hundred years ago--even 50--the wider world scarcely knew of Ayers Rock. But an estimated 350,000 visitors entered Uluru Kata-Tjuta National Park last year, and most of them tried to climb the rock. As it and Australia’s other attractions brace for the global attention that next year’s Sydney Olympics will bring, the tourist numbers here are bound to grow.

It’s risky and rude to treat the rock as a simple playground. One or two climbers die every year, rangers say, either from heart failure or a fall. The Aborigines who own the rock would rather tourists didn’t climb it at all. And the surrounding high, dry plain stretches for hundreds of miles in every direction, the most thinly populated territory in one of the most thinly populated nations on Earth.

Yet these days, a visitor to Uluru leads a strangely easy life. True, a snap-and-dash tourist will be frustrated by airline flight schedules that seem calculated to force a stay of at least one night, and there’s no evading the flies, which prompt many hikers to drape netting from their new leather hats. But from the moment of arrival at the Ayers Rock airport (three hours and 35 minutes by air from Sydney), tourists land in the hands of a smooth-running enterprise.

It begins with the free shuttle buses that rush travelers to the Ayers Rock Resort, a low-lying, self-contained citadel about 12 miles north of Uluru. The resort includes six restaurants, four bars, a child-care center, police department, cinema, library, camel depot, more than 630 hotel rooms, scores of dormitory beds and two campgrounds. Room prices range from $15 a bed (in the dorms) to $250 a night (in the Sails in the Desert Hotel, where a renovation is due to be completed in April).

I stayed in the quiet, agreeable Desert Gardens Hotel, second best in the resort, where the biggest surprise was the grasshopper that jumped out of my minibar.

The eating options run from the picnic tables and cook-your-own barbecue grills at the Outback Pioneer Hotel to the Sounds of Silence, a nightly dinner excursion to a desert spot where champagne, planet-hunting by telescope and didgeridoo music is offered alongside a cloth-napkin, candle-lighted dinner under a star-bright sky.

Because camping in the park is forbidden, the resort acts as headquarters for virtually everyone within 100 miles of the rock. The year-round population of resident staff is about 1,000--five to 10 times the size of the Aboriginal community by the rock. Yet the resort blends into the desert so well that it’s difficult to spot even from atop Uluru.

Dawn at the rock.

“Wow!” whispers a boy of about 10.

“It’s like a big brain,” says a woman near him.

“It’s like a cake with dripping frosting,” says a man.

The Northern Territory that surrounds Uluru, wrote Australian author Banjo Paterson in 1898, is “a vast half-finished sort of region, wherein Nature has been apparently practising how to make better places.”

Those miles of raw outback were so unencouraging that no Westerner reached the rock until 126 years ago, when pioneers strung up the first north-south telegraph connection through the outback. One day in 1873, an explorer named William Christie Gosse found himself about 280 miles southwest of the telegraph town of Alice Springs, looking at a very big, very red rock. He named it for the chief secretary of South Australia at the time, Sir Henry Ayer.

But next to Uluru dwelt Aborigines, descendants of the Pitjantjatjara and Yankunytjatjara peoples. These Aboriginal communities, broadly known as Anangu, have lived in the neighborhood for at least 22,000 years.

In 1920, after ranchers failed to wrest a profit from the area, Australian government officials set the rock aside as part of a reserve for Aboriginal people. But in 1958 the government took that land back and made the rock the centerpiece of a national park.

The Anangu’s ancestors, who named the rock Uluru, wove a religion and oral tradition around the monolith and discovered life-sustaining uses for nearly every animal and plant in the high desert. They also found the path up the rock--the same path now marked by steel posts and the white dotted line.

The path, the Anangu leaders say, “is of great spiritual significance. We have a duty to look after visitors on our land and feel a great sadness when a person dies or is hurt on the climb.”

By the late 1960s at the rock, an airstrip, motels and paved roads had begun doing their work, and the annual tourist figure had reached 23,000. By 1984, the new resort had replaced the old motel complex, the annual visitor count had passed 100,000 and Ayers Rock had a new reason for notoriety.

In August 1980, a 9-week-old girl named Azaria Chamberlain vanished from a tent near the rock and was never found. The child’s mother, who insisted that a dingo took her daughter, was jailed for more than three years in connection with the case. But ultimately, after eight years of legal battles and a film starring Meryl Streep (“A Cry in the Dark”), both parents were acquitted.

Like Native Americans, Aboriginal activists have won major legal victories in recent decades. The biggest might be the 1985 handing back of the rock. As part of the Australian government’s return of the rock to its original owners, Anangu leaders agreed to lease it back for 99 years to the Australian National Parks and Wildlife Service.

The deal gives aborigines 25% of park revenue, but excludes a ban on climbing. And so the store in the Uluru-Kjuta Cultural Centre near the rock peddles not only didgeridoos, boomerangs and artworks but bumper stickers that proclaim “I didn’t climb Uluru.”

Just a few days before I arrived, Australian Deputy Prime Minister Tim Fischer visited and urged tourists not to climb, thereby setting off a nationwide flurry of letters to the editor (one of which suggested that tourists would climb the Sydney Opera House if authorities let them).

Still, each day the tourists nod as the Anangu position is explained, then climb skyward. Park rangers say they think more visitors are staying below, but numbers are hard to come by.

Even indoors, the rock casts a shadow over behavior patterns. Hotel lobby signs note daily sunrise and sunset times, predict high temperatures (102 Fahrenheit on the January day I arrived), urge consumption of one quart of water per hour outdoors.

Step into the Tour and Information Centre next to the Spinifex Lodge, and you’re surrounded by booths run by the dozen tour companies whose business is built around the rock: Frontier Camel Tours, Professional Helicopter Services, Uluru Motorcycle Tours (leather jacket, helmet and gloves provided) and so on.

At one end of the room, most days, sits Deanna Virgona, booking officer for Aboriginal-owned Anangu Tours and an opponent of climbing. In a typical year, she said, the company’s Aboriginal guides lead perhaps 10,000 tourists on non-climbing tours.

About 10 paces across the information center stands the booth of the resort’s most powerful tour operator, AAT Kings, which runs the free buses from the airport and ends up shaping most visitors’ itineraries.

Each day AAT Kings circulates two dozen air-conditioned buses, carrying guests to the rock, the Aboriginal cultural center and also nearby Kata Tjuta, an unearthly eruption of 36 massive domed rocks from the desert floor also known as the Olgas.

And each day, like those travelers who inch their way up the steep surface of the rock, AAT Kings walks a fine line.

The company proclaims itself “a major supporter of culturally aware touring,” yet includes a climb of the rock in four of its 10 local tours.

It bans its own guides from climbing the rock while in uniform and even helps promote non-climbing tours run by aboriginal-owned Anangu Tours. But AAT Kings brochures offer “Ayers Rock Climbers Certificates” to anyone who reaches the top of Uluru.

If I were on a true vacation, I might have passed on the climb and chosen instead to make the six-mile, three-hour hike around the rock, or maybe even splurged on a helicopter ride. But I wanted to hear what the people on the rock had to say, and I wanted photographs. Also, once I had started, I wanted the satisfaction of finishing. Up I went.

At first, all I heard was panting. Within 20 steps, the trail’s steepness has most hikers gasping. Among the more than 30 deaths recorded at the rock, rangers say the most common cause is heart failure provoked by the strenuous climb, often aggravated by dehydration.

The determined climbers stop periodically, find a place to sit, sip their water bottles and suck air. Others just turn around and come right back down. One climber in his 20s, a tall, fit Bostonian named Mike Cabral, covered a few hundred yards, then retreated. It wasn’t fatigue, he told me later; it was fear of heights.

Uluru stands 2,831 feet above sea level, 1,115 feet above the surrounding plain. The rock typically takes about an hour to climb, another hour to descend. On days when the temperature is expected to reach 100--common during the Australian summer months of January and February--rangers close the rock to climbers from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Though the desert below looks profoundly desolate, the last census found 416 plant species in the area, 250 species of birds and reptiles, 25 species of mammals.

The morning I climbed, about one in four humans on the rock seemed to be Japanese. Near the top, I agreed to take a photo of a young Japanese couple. Just as I was about to snap their picture, the young woman flung out her arms, fixed her gaze on the horizon and assumed the Titanic position: a regal Kate Winslet bow pose, her fingers flashing peace signs as a bonus. Click.

After the rock, every visitor’s next destination seems to be Kata Tjuta, also known as the Olgas. That rock formation stands 25 miles west of Uluru, within the same national park, and the highest of its domes is about 670 feet higher than Uluru.

Kata Tjuta’s spiritual significance to Aboriginals may be even greater than Uluru’s: Only initiated Anangu men are permitted to learn certain myths and visit certain sites, and none of the domes can be climbed. Two popular routes, the 3 1/2-mile Valley of the Winds trail and the half-mile Olga Gorge path, take hikers between the domes.

Still, the rock has a singular attraction.

“It’s not what I expected at all,” said a man from Melbourne at the bottom, panting between sentences. “It’s bigger. And better. And it’s smoother.”

“Cecil B. De Mille,” said his wife, gazing up, “eat your heart out.”

The next morning I joined an Anangu guide, an interpreter and a handful of other visitors who’d signed up to learn about Anangu culture and bush skills. I’d heard glowing reports from another visitor who’d felt a gratifying connection with the Anangu woman who’d led a similar tour.

At the cultural center, we met our leaders: The bright young interpreter named Mark stood protectively alongside Millie, a painfully shy middle-aged Anangu woman who seemed to understand English but scarcely spoke. The rest of the morning was an education in A) how far removed English-speaking and Anangu cultures remain; and B) why so much uncertainty persists over the question of climbing Uluru.

The rock’s place in local Aboriginal culture is difficult for an outsider to grasp: The Anangu system of spirituality is closely tied to geography, and the oral tradition is sustained by stories that simultaneously demonstrate local geography, trace animals back to mythic personas and teach values like honesty and courage. A handful of especially revered areas near the rock are fenced off from visitors.

For two hours, Millie and Mark made a tenacious team. Millie, strolling barefoot in the bush without hat or sunglasses, would offer up a few syllables or wordlessly demonstrate a bush skill, then retreat to the shade of a gum tree. Then Mark would step up and conjure her few words into a full presentation on how to make glue from plants, or fire from sticks. On we walked in the red dust, learning plenty from Mark and scarcely glimpsing the whites of Millie’s eyes.

I tried sidling up to Millie myself to ask about the rock climbers, but only a few syllables came back, and no insight. So much for making my three-day visit into a great cross-cultural leap.

But maybe it shouldn’t be surprising that Millie and the rock have grown alike out here in the desert. They’ve seen plenty, they’re not inclined to discuss much, and once we’ve paid our visit and caught our flights out, they’ll still be here.

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX / INFOGRAPHIC)

GUIDEBOOK

Getting a Piece of the Rock

Getting there: In the shoulder season beginning March 1, round-trip fares from LAX to Uluru/Ayers Rock, connecting through Sydney, start at $1,707 (excluding taxes) on Qantas Airlines.

Where to stay: The Ayers Rock Resort (central reservations telephone 011-61-2-9360-9099, fax 011-61-2-9332-4555) includes Sails in the Desert Hotel (standard double rooms about $250 nightly), the Desert Gardens Hotel ($210), Emu Walk Apartments (one-bedrooms $195), Spinifex Lodge (standard rooms about $85) and the Outback Pioneer Hotel & Lodge (standard rooms $185, dorm beds $15-$20).

For more information: Aussie Helpline; tel. (661) 775-2000, fax (661) 775- 4448, Internet https://www .australia.com.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.