Beyond Apologies, Stamp Out Syphilis

- Share via

President Clinton’s apology to a handful of survivors of the infamous Tuskegee experiment, in which African American men with syphilis were left untreated as part of a government study, is long overdue. But it should be merely the first step toward addressing racial inequities in the rates of sexually transmitted diseases like syphilis that have been a national epidemic for more than 50 years.

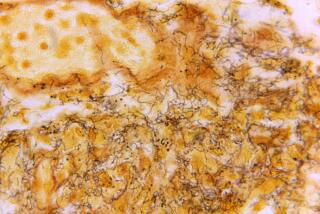

The Tuskegee study, carried out in Alabama from 1932 to 1972, tracked nearly 400 poor black men with syphilis to learn about the disease. Untreated, syphilis can lead to the degeneration of bones, nerves and heart and can be fatal. When penicillin offered a cure for syphilis in 1947, researchers continued to withhold treatment from the study subjects. Public outcry finally led to an investigation and the study’s termination. By the end, however, at least 28 of the men died as a result of untreated syphilis.

Having acknowledged this hard lesson in ethics--that withholding effective treatment is immoral--Washington must heed Tuskegee’s further imperative: a determination to eradicate syphilis in the United States once and for all.

People of color in the United States are still disproportionately affected by sexually transmitted diseases, including syphilis, gonorrhea and chlamydia. In Los Angeles County, African Americans are 15 times more likely and Latinos four times more likely to acquire such diseases than white Americans. Higher rates of syphilis among African Americans have resulted in a markedly increased risk of congenital syphilis, fetal and infant mortality and HIV transmission to babies born to black women.

Ironically, renewed interest in addressing the wrongs of Tuskegee comes at a time when available public health services for prevention and treatment are being dismantled. For six years there has been no increase in federal funds to contend with gonorrhea and syphilis--allowing for inflation, that’s effectively a 20% cut. State and county programs on sexually transmitted diseases nationwide are being threatened with an additional 7% funding cut next Jan. 1.

For Los Angeles, such cuts are especially damaging. The L.A. County Department of Health Services is still reeling from a major fiscal crisis in October 1995 that led to the closure of 18 of the 28 county sexually transmitted disease clinics, reducing clinic access in geographical areas with the highest rates of disease. The exact consequences of these cuts remains unknown, but their impact is clear: reduced health service delivery leading to increased levels of such diseases.

A further irony is that these funding cuts are being proposed at a time when there is a realistic chance of eliminating syphilis. Syphilis has been virtually eliminated in two-thirds of U.S. counties. Sustained efforts to eradicate syphilis are especially critical in large cities like Los Angeles. Without such efforts, we risk a resurgence of epidemic syphilis, entailing new waves of HIV transmission and new outbreaks of congenital syphilis in poor minority communities. With highly effective and inexpensive tests and treatment for syphilis, these communities should no longer have to suffer a disproportionate toll from this disease.

Whatever comfort the survivors of the Tuskegee study and their families may draw from Clinton’s apology, the best memorial to the men who died would be a true commitment to funding and resources to combat sexually transmitted diseases and eliminate syphilis in the United States.