Limits on Baptism of the Dead Shake Mormons

SALT LAKE CITY — When Mormon leaders agreed recently to stop baptizing Jewish Holocaust victims posthumously, it signaled a fundamental change in a practice Mormons hold dear.

For decades, fervent members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints have made regular trips to their temples to perform the sacred rite of baptism for historical figures they venerate or dead people whose lives had no link to their own.

But in an agreement with several Jewish groups, Mormon leaders pledged to scale back that practice to its original dimensions, and return--as Elder Monte Brough told Holocaust survivors--to a position declared by church doctrine: that the Mormon rite of baptism for the dead be accorded only to the ancestors of current Mormons.

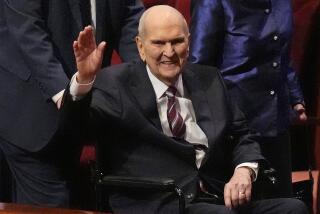

His statement surprised many Mormons, because that’s not the way it was in the 1970s, 1980s and early 1990s. Apparently, though, it’s the way the church’s governing First Presidency--new President Gordon B. Hinckley and his two counselors--want it to be.

“The big task the First Presidency has given me is to bring under some control this whole idea that members can just extract various names” from historical records and baptize them as Mormons, said Brough, director of the church’s Family History Department.

Vicarious baptism of the dead is no small matter to Mormons. The services are considered a solemn obligation and blessing for the living, and an offering of the Mormon mantle to those no longer living but existing in a spirit world.

Baptizing the dead is a central tenet of the Mormon Church, which believes the practice gives every spirit a chance to accept or reject baptism in the “true Church of Jesus Christ.”

But Jewish leaders took offense following revelations that many of those baptized by proxy were Jews who had died during the Holocaust because of their religious faith.

After discussions between Mormon and Jewish leaders, Mormon church officials agreed to direct all members to discontinue future baptisms of deceased Jews, except those who are ancestors of living church members or whose families give permission.

The crucial importance of the ritual to Mormons put the church in an uncomfortable position in the middle of this century, according to a new book, “Hearts Turned to the Fathers,” which explains how the church developed the world’s largest genealogical library to support its work for the dead.

Church doctrine had always required members to trace their ancestry and perform the ritual for their own ancestors. But because of lack of training, research sources and time, few members could complete their family genealogies. And even those who could did not produce enough names of the dead to keep up with the demand at the temples.

So in 1961, the church began extracting names from the microfilmed records and oral histories the church was collecting from around the world for its library.

“It was not a shift in doctrine. It was a recognition that ‘Why shouldn’t we be doing temple work for any names of those who have passed?’ The idea being that every son and daughter of God will have the chance to accept or reject the concept,” said James B. Allen, one of the book’s co-authors and a senior research fellow in church history at BYU.

Over the years, rules governing members’ submission of names for baptism were liberalized, and by 1981 members were allowed to submit names of people they had no relation to, as long as the person had been dead for nearly a century or the family gave permission.

But Brough, who took over the Family History Department in 1993, said many of those submissions were made without regard to family wishes.

“Frankly, we as church leaders [have] . . . allowed a little slack in this,” he said. “There’s some tightening up that we have to do.” Now, members will have to stick with their own ancestry, or with names of persons likely to be ancestors.

Brough said modern-day Mormons are carrying out the mandate of church founder Joseph Smith, who said, “Our dead cannot be saved without us and we cannot be saved without them.”

“It is fundamental to our whole existence,” Brough said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.