NEWS ANALYSIS : The Only Thing That Developed Was Chaos : City Council: It was prearranged harmony--a public display of SMRR’s restored unity. But the scripted agreement on development standards had a surprise ending. Now the city is faced with little time to do much about its zoning dilemma.

SANTA MONICA — Did you catch “The Ken and Judy Show” Tuesday night?

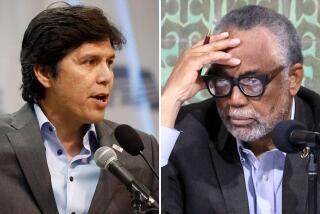

That’s Santa Monica Mayor Judy Abdo and Councilman Ken Genser, who performed a marathon duet at the City Council meeting.

The two were clearly singing harmony as they unveiled an obviously prearranged compromise they had struck over the citywide commercial development standards.

It went like this: Abdo called on Genser each time a new subject arose. He offered an amendment. She said, “That’s friendly.”

And so on for hours.

Until it blew up in their faces, leaving the staff stunned and the city stranded without new development standards and very little wiggle room to enact them before a looming deadline.

Here’s what happened.

The city has been operating for five years under an “emergency” moratorium on commercial development, which expires at the end of the month. That means property owners have been unable to develop their land for all that time.

(Any new commercial construction seen in the past few years in Santa Monica was approved before the development blackout.)

Five years is unusually long for such a moratorium; officials say they know of no other city that has had one of such duration. And the city’s top lawyer finds it worrisome.

City officials say a five-year “emergency” is apparently hard to sell in court if developers sue. The word emergency “implies a certain temporariness,” explained acting City Atty. Joe Lawrence, who has repeatedly warned the council that extending the ban further could put the city in an untenable legal position.

But that was all supposed to be resolved at Tuesday’s meeting. No one expected fireworks, because the standards were thought to be a “done deal”: The council had voted for the amount of development they wanted in various zones of the city a month ago, and Tuesday’s proceedings were expected to be little more than a formality.

Several days before the meeting, however, an unexpected sequence of events upset the apple cart, and a bid for unity spawned chaos.

Rifts have existed in the city’s powerful renters’ rights movement for several years, traced to battles over two ill-fated developments--a beach hotel project and a large office complex at Santa Monica Municipal Airport.

Although the disagreements were patched up enough to allow the renters’ coalition to remain in power in last November’s council election, the cracks have been showing again in a most public way. Responding to published reports of open warfare among the council members they helped elect, the steering committee of Santa Monicans for Renters Rights (SMRR) called a meeting late last month. According to several sources, council members were rebuked about their antics and overall lack of accord.

SMRR-aligned council members Abdo, Genser and Paul Rosenstein were told by the leaders of their political alliance that further public squabbling would harm the group’s election prospects. They now are part of a 5-2 majority on the council, which often doesn’t help if the five can barely agree on what day it is.

As it happened, the development standards were on the agenda of the first council meeting after the SMRR unity session. The standards thus became a convenient issue on which the warring council members could display their supposedly repaired relationship.

Predictably, the proposed standards have been the target of criticism. Some business people said the standards, significantly tougher than the last citywide zoning standards set in 1988, were too strict. The stringent slow-growthers thought they were too lenient.

By most accounts, Abdo agreed after the SMRR committee meeting to make some concessions to Genser on the zoning standards, even though her more moderate views had carried the day a month earlier.

Abdo said that by reopening the deal, she also got more of what she wanted--incentives for housing. But most observers think Genser got by far the better bargain. He refused comment.

The details of the compromise were hammered out in a second private meeting a few days after the SMRR unity meeting. The city’s surprised professional planning staff said they didn’t see the wholesale changes until the morning of the council meeting.

The staffers hastily hand-drew a chart that depicted top-to-bottom changes in the zoning ordinance. It was passed out to council members after the meeting had already started, allowing no time for anyone to review it.

And of course, no one in the public could study it either.

But that wasn’t supposed to matter, because the five SMRR council members were all lined up to approve the compromise after the “Ken and Judy Show” was over.

The show bombed, however, because the players misjudged their audience.

“Unity fell apart in two or three minutes,” one observer said. But no one realized it at first; in fact, it took nearly five hours for the extent of the problem to reveal itself.

Knowing early on that he had been snookered, Councilman Robert T. Holbrook complained about a back-room deal and caustically told his colleagues to let him know when their show was over so he could participate.

Abdo responded that he was seeing the council “working together.”

Then, not knowing when enough was enough, Genser pushed the envelope with a whole new plan to limit one of his least favorite businesses--car repair shops. It was not part of the deal with Abdo and irritated at least three members of the council--Rosenstein, Holbrook and Councilwoman Asha Greenberg.

“I have a real problem with the ways these things come up,” Greenberg said. “We come here to vote for one thing and new things come up.”

Greenberg and Holbrook, the only two council members not part of the SMRR alliance, are, in fact, frequently out of the loop. Often they are treated dismissively, and this time it happened in a very public way.

But with a little help from their political foes, they managed to turn the tables.

Though the council had spent hours detailing the zoning compromise, they had left the most essential issue till last--the vote on whether to approve the environmental impact report.

Without that approval, no compromise would matter, because the council could not legally adopt either the standards they had voted on a month ago or the Abdo-Genser compromise.

Again, though, the vote to approve the impact report was expected to be a slam-dunk. Genser and Councilman Kelly Olsen routinely voted against them as part of their slow-growth agenda, a luxury they are usually afforded because they know everyone else will vote “yes,” and the plans can move forward.

So everyone was expecting a 5-2 vote for the report.

Then the scorned outsiders got even. Greenberg and Holbrook called Genser and Olsen’s bluff by voting with them to reject the impact report. Rosenstein also voted no, because he said the document overstates impacts, making those who favor it appear to the community as pro-development.

Abdo and Councilman Tony Vazquez were left holding the bag on a 5-2 vote against certifying the report, a legal hurdle that must be met before any guidelines can be passed.

“Bob and Asha probably were seething at watching the steamroller coming down the street,” Rosenstein said. “Then they put up a brick wall in front of the steamroller.”

Abdo pleaded with the others to reconsider. “All the work we’ve done this entire meeting has been for nothing,” she said. “Nobody is going to come and rescue us.”

Indeed, city planning officials Paul Berlant and Suzanne Frick briefly abandoned their usual aplomb at the meeting to gawk open-mouthed at the turn of events. The two attorneys involved looked similarly stricken.

“The staff was surprised and frustrated,” Berlant said. “A lot of work has been put into this and a lot of public expectations have been raised.”

By week’s end, nothing had been resolved. Without an approved environmental impact report, the process is paralyzed. A new report would take at least six months and $50,000 to prepare, on top of the $100,000 already paid to consultants for the old report.

If the development moratorium runs out, the zoning standards revert to the 1988 rules. Holbrook said that would be all right with him, but certainly not with the SMRR council majority that has been leading the charge for less development.

So the SMRR majority is caught in a dilemma: An extended moratorium invites legal trouble, and doing nothing means certain political trouble.

City political observers expect major lobbying and heavy arm-twisting over the next few weeks. Current wisdom suggests that Genser and Olsen won’t budge on their vote against the environmental impact report. Rosenstein may ultimately be shamed into changing his vote for the sake of the SMRR family.

But that’s only three votes, not four.

Greenberg or Holbrook--or both--must also be appeased.

And that’s how two council members, who started out being ignored, wound up producing a show of their own.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.