COLUMN ONE : Time to Die for Killer Virus? : Smallpox, a scourge for centuries, is near extinction. Scientists must decide whether to destroy the last few vials--amid claims of human achievement, arrogance.

Nestled in the bowels of a government laboratory in Atlanta, in a tiny room under constant electronic surveillance, a padlocked silver-and-blue freezer houses a set of vials whose contents, if let out, could unleash upon an unprotected world one of mankind’s deadliest plagues.

More than 5,000 miles away at a scientific institute in Moscow, a similar collection sits, frozen in liquid nitrogen at minus 94 degrees Fahrenheit, guarded by police around the clock.

Together, these ampuls contain the legacy of one of the most remarkable accomplishments in the annals of medicine: the eradication of smallpox, the only disease ever wiped out by man. The vials at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Russia’s Research Institute for Viral Preparations contain the only known specimens of a virus that altered the course of history, felling paupers and kings, soldiers and tribesmen and untold millions who had the misfortune to cross its path.

Now, scientists are grappling with a unique and confounding question: Should the last, locked-up remnants of smallpox be destroyed? Should the world’s biggest mass murderer be sentenced to death?

“It is a monumental decision,” said Dr. Giorgio Torrigiani, director of communicable diseases for the World Health Organization in Geneva, which has recommended destroying the virus after U.S. and Russian scientists finish charting its genetic makeup this year. “It’s the culmination of the success that we had in wiping out a disease that was a dreadful disease for many, many centuries. This would be the last step.”

It would also be a significant first step. If the smallpox virus is obliterated, it would mark the first time that man has ever intentionally rendered a species extinct.

A final decision is expected from WHO by the end of this year. Although officials at the agency--which orchestrated the successful global campaign to stamp out smallpox--see great symbolism in their plans, critics argue that the destruction would stand not as a shining example of humanity’s success in conquering disease, but as a disturbing reminder of our arrogance.

“I think there is a certain amount of hubris inherent in the human view that we can dominate nature, that we own nature,” said medical ethics expert Arthur Caplan of the University of Minnesota. “Smallpox doesn’t look like it’s done anybody any good in the history of humankind. But it seems to me we would be too arrogant and too shortsighted if we just assumed that the creatures that tried to kill us would forever be our enemies.”

The debate, which will take center stage this summer when 5,000 virologists convene at the International Congress of Virology in Scotland, is framed by a host of questions:

If the virus is kept, what is the potential for a laboratory accident? Could it be used as a biological weapon--and a particularly deadly one, given that routine smallpox vaccinations stopped shortly after the disease was officially certified as obsolete on May 8, 1980.

On the other side of the issue: Would wiping out a species, even one as despised as smallpox, set a dangerous precedent? Will cracking the genetic code tell researchers all they need to know about the virus, or will killing smallpox mean burying important scientific secrets forever? Could there be, as Caplan suggests, some beneficial use for the virus that we cannot foresee?

Such abstract arguments may seem more in the realm of philosophy than science. Nonetheless, they are helping to shape the debate over whether smallpox should be condemned to die in an autoclave--a sort of scientific equivalent of the gas chamber.

“We are just beginning to understand the functions of the genes of viruses that belong to this class,” said Bernard Moss, a virologist at the National Institutes of Health who has made a career of studying viruses in the pox family. “It may be that five years from now, or 10 years from now, we will have a question and we will either need access to the DNA of the smallpox virus, or the smallpox virus itself.”

*

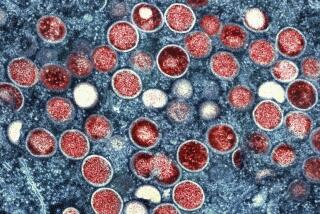

If ever there were an unpopular species to defend, smallpox is it. It is a nasty little bug, carried in microscopic airborne droplets inhaled by its victims, and it has wrought upon millions a singularly horrible death. Only humans can contract it.

The first signs were headache, fever, nausea and backache, sometimes convulsions and delirium. Soon, the skin turned scarlet. When the fever let up, the telltale rash appeared--flat red spots that turned into pimples, then big yellow pustules, then scabs. Smallpox also affected the throat and eyes, and inflamed the heart, lungs, liver, intestines and other internal organs.

Death often came from internal bleeding, or from the organs simply being overwhelmed by the virus. Survivors were left covered with pockmarks--if they were lucky. The unlucky ones were left blind, their eyes permanently clouded over.

Nearly one in four victims died. Egyptian Pharaoh Ramses V--the first documented smallpox sufferer--lost his life to the virus in 1157 BC. Marcus Aurelius Antonius, the Roman philosopher-emperor, was another probable victim; during his reign smallpox wiped out 2,000 people a day.

During the 16th Century, 3.5 million Aztecs--more than half the population--died of smallpox during a two-year span after the Spanish army brought the disease to Mexico. Two centuries later, the virus ravaged George Washington’s troops at Valley Forge. And it cut a deadly path through the Crow, Dakota, Sioux, Blackfoot, Apache, Comanche and other American Indian tribes, helping to clear the way for white settlers to lay claim to the western plains.

The epidemics began to subside with one of medicine’s most famous discoveries: the finding by British physician Edward Jenner in 1796 that English milkmaids who were exposed to cowpox, a mild second cousin to smallpox that afflicts cattle, seemed to be protected against the more deadly disease.

Jenner’s work led to the development of the first vaccine in Western medicine. While later vaccines used either a killed or inactivated form of the virus they were intended to combat, the smallpox vaccine worked in a different way. It relied on a separate, albeit related virus: first cowpox and then vaccinia, a virus of mysterious origins that is believed to be a cowpox derivative.

Thus even if the smallpox virus is destroyed, the vaccinia virus--which gave its name to the word vaccination-- will remain, should smallpox vaccines ever need to be formulated again.

By the early 1800s, tens of thousands of people were being inoculated with Jenner’s vaccine. Even so, smallpox continued to afflict Americans and Europeans well into the 20th Century. It also wrought havoc in Africa, India and other underdeveloped parts of the world until, after a massive, decade-long global health initiative, the last case of naturally transmitted smallpox was documented in Somalia in 1977.

That year, the disease met its ignoble end in the body of a 23-year-old hospital cook named Ali Maow Maalin, who contracted it, and thus earned a place in the medical history books, as a result of his own kindness--he took an infected child for treatment. The child died; Maalin survived.

Maalin’s, however, was not the last case. In September, 1978, an English laboratory accident exposed a 40-year-old medical photographer named Janet Parker to smallpox--an incident that has lent credence to arguments to destroy the remaining vials. Parker died. Her death had a ripple effect: The virologist in charge of the laboratory was so despondent over her fate that he killed himself.

With so much carnage in its wake, smallpox finds few advocates among virologists and microbiologists who have made a career of studying the disease. No scientific organization or agency has stepped forward to take up its cause.

“Smallpox has killed a lot of people and so anything we can do to limit an accidental release, I’d be in favor of,” said Kenneth Berns, a microbiology professor at Cornell Medical College who is organizing a discussion on the issue at the virology conference in Scotland this summer. Berns said he expects to have some trouble drumming up the opposite view: “The countervailing arguments are not overwhelming.”

The American Society for Virology and the American Society for Microbiology have voted in favor of destroying the vials. The American Type Culture Collection--a nonprofit group that is dedicated to the preservation of microorganisms--made an exception to its policy and recently authorized the CDC to destroy stocks of smallpox virus that it turned over to the government for safekeeping.

Even some ecologists--who hailed President Clinton’s signing of an international biodiversity treaty as an important step toward maintaining the world’s ecological balance by protecting its varied species--are apparently uncertain about smallpox. In the debate over biodiversity, experts say smallpox is cited to demonstrate that not every species is worthy of being spared.

“It is used as an absurd case in the minds of some, (who argue): ‘You don’t really believe, do you, that the virus should be saved?’ ” said Holmes Rolston III, an expert in environmental ethics at Colorado State University. “It represents the kind of extreme test case about the reverence for life.”

Still, there are outspoken defenders. They include Moss of the NIH; Donald Hopkins, a former CDC official who, like Moss, argues that scientists might find a future use for the virus, and Samuel Kaplan, a microbiologist at the University of Texas who says destroying the virus will start science on a dangerous slippery slope toward the intentional extermination of other species--whatever might be unpopular at the time.

“One might argue that this virus is such a terrible thing that one really wants to do this,” Kaplan said. “Well, there are lots of other terrible things around. And the question is, if one has the ability to do this with other systems, whether they be viruses or bacteria or fungi, do you do it or don’t you do it? I think that once you do it one time, it becomes just a wee bit easier to do it the second time around.”

Scientific and philosophical debates aside, the impetus to eliminate the last vials of smallpox has its roots in Cold War politics, according to D. A. Henderson, who spearheaded the campaign for WHO and was recently named by Clinton as deputy assistant secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services.

Henderson said the idea of destroying the remaining vials emerged in the late 1980s, before the collapse of the former Soviet Union, when leaders of developing nations expressed fears that the virus could be used by the superpowers in biological warfare. Although arms experts say smallpox would be an inefficient biological weapon, the United States, Russia, Canada and Israel have continued to inoculate soldiers against the disease--just in case.

By that time, the world’s remaining stocks had been consolidated into the two collections. The CDC keeps about 400 different strains, and the Moscow laboratory 200.

In May, 1990, then-U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary Louis W. Sullivan announced that the United States would destroy its remaining smallpox stocks after scientists had unlocked its genetic code. He invited leaders of the former Soviet Union to do the same, and they agreed.

An ad-hoc committee of the World Health Organization subsequently recommended that smallpox be destroyed. The panel set this December as a target date and agreed to take up the matter one final time once the gene sequencing project is finished and the results are made public.

Already, U.S. and Russian scientists have plotted the genetic blueprint of two complete strains of the extremely complex smallpox virus, although they have not yet published their work. The scientists are studying unique regions of several other strains.

Their research will provide valuable insight into how the virus interacts with cells, which proteins enable it to avoid the body’s immune system so successfully, and how it differs from other viruses, such as cowpox, that are similar but not as deadly.

Although scientists could theoretically synthesize the virus once its genetic sequence is known, experts say the task would be nearly impossible because smallpox is so complex. Moreover, the gene sequencing will not answer every question about smallpox, said Robert Massung, the CDC researcher directing the project.

“The real question is how it managed to avoid the immune system, how it managed to cause such a severe disease that was only an infection in humans,” he said. “Those are the types of things you can never find out. You can’t do it without infecting individuals, and there aren’t too many volunteers.”

It took the CDC researchers 18 months to identify the 185,000 pairs of chemicals--the so-called DNA bases--that form the genetic blueprint of a particularly virulent strain that erupted in Bangladesh in 1975. Although it was time-consuming, the endeavor was relatively safe; the scientists work with non-infectious DNA, which is extracted from the supplies of live viruses in Atlanta and Moscow.

Massung bears the distinction of being the last person in the world to come into direct contact with the live virus. Two years ago he suited up in a thick, sealed baby blue spacesuit so that he could grow a South American strain of the virus and extract its DNA, which his Russian counterparts needed for their work.

If that sounds like high drama, Massung and other government scientists who serve as the American custodians of smallpox are decidedly blase about the possible execution of the virus to which they have devoted their careers. They are loathe to offer their opinions about its possible demise, saying only that they will follow the decision of the World Health Organization.

“My view is neutral,” said Joseph Esposito, Massung’s boss at the CDC. “I’m too close to the project. My personal opinion really doesn’t matter.”

Even Henderson--whose name is synonymous with smallpox eradication in the scientific community--said he is ambivalent about doing away with the virus.

“If I were to put on my scientific hat and say what would I do, I would say: ‘Keep the virus,’ ” Henderson said. “I think the risk of it escaping by any means is close to zero.”

But on the other hand, he said, he understands that even though the Cold War is over, politics will inevitably come into play.

“If I look at it from the standpoint of political concerns and apprehensions on the part of a number of countries, I don’t think its easy for them to understand (that smallpox poses a minimal risk). . . . A lot of people have said to me: ‘Why don’t we destroy it so there is no risk?’ ”

As the debate continues, the virus awaits its fate. If the end comes--and Henderson and others agree that it probably will--smallpox is likely to be steamed to death under extreme high pressure in an autoclave, with a small crowd of independent scientists witnessing the execution for the sake of security, and posterity.

Really, they say, it would all be very simple. With little more than the push of a button, smallpox, friend to none, could be gone for good.

Smallpox’s Deadly History

A chronology of key events in the history of smallpox:

* 1157 BC: Egyptian Pharaoh Ramses V dies. He is the first documented smallpox sufferer.

* 1500s: 3.5 million Aztecs--more than half the population--die during a two-year span after the Spanish army brings the disease to Mexico.

* 1700s: Smallpox ravages George Washington’s troops at Valley Forge and attacks many American Indian tribes.

* 1796: British physician Edward Jenner discovers that milkmaids exposed to cowpox are protected against the more deadly smallpox. This discovery leads to development of the first vaccine in Western medicine.

* 1800s: Tens of thousands are inoculated with Jenner’s vaccine, but well into the 20th Century smallpox remains a threat around the world.

* 1977: After a global initiative, the last case of naturally transmitted smallpox is documented in Somalia in 1977. A hospital cook survives after caring for a sick child, who dies.

* 1978: The last known death from smallpox occurs. An English medical photographer dies after she accidentally is exposed to the virus in a laboratory.

* 1980: Smallpox is officially certified as obsolete on May 8.

* 1990: The U.S. government announces that it will destroy its remaining smallpox stock once scientists have unlocked the virus’s genetic code. Leaders of the former Soviet Union agree to do the same.

* 1993: A World Health Organization panel sets a December target date for decision on whether to eradicate smallpox.