NEWS ANALYSIS : More Turmoil for Venezuelans : South America: The president may be impeached on corruption charges. His term has less than a year to go.

CARACAS, Venezuela — After surviving two military coup attempts, deadly street riots and severe economic shock, this nation has plunged itself into another, seemingly self-induced political crisis with the possible impeachment of President Carlos Andres Perez--even though he is due to leave office in less than a year.

Atty. Gen. Ramon Escovar Salom, once Perez’s foreign minister but now among his bitterest critics, has filed charges with the Supreme Court, seeking the president’s impeachment on grounds that he misappropriated $17 million of public money.

The possibility of Perez’s impeachment coincides with violent demonstrations throughout the country and a daily blitz of rumors of a coup by radical middle-ranking military officers, a preemptive coup by conservative senior officers or a self-coup by Perez.

The result has been near public panic, serious destabilization of the political process and a near shutdown of the government.

“Venezuela is dancing with chaos,” said a leading constitutional lawyer here. “We are (South) America’s oldest functioning democracy and the richest, but we can’t seem to stop mutilating ourselves.”

Perez has been the subject of vehement criticism for his dramatic shift from a heavily subsidized, protected economy to an open, free-market system and for allegedly engaging in major corruption.

Besides those factors, a general feeling exists among many here that the entire political structure is inept, that most politicians and Establishment figures are personally corrupt and that the Venezuelan middle class has suffered serious economic loss.

While public discontent is deep and wide, the anger has settled almost entirely on Perez, 70, who won an overwhelming electoral victory four years ago. His public approval figures in the polls fluctuate in the teens, and all but his closest allies in his Democratic Action party have deserted him. His one-time popularity has dissolved in the face of corruption charges and a widespread perception of arrogance and disdain.

But his impeachment is no certain thing. The law requires the Supreme Court first to decide if there is a basis for charges against Perez. If so, the case is turned over to the Senate, which decides if there should be a trial. If so, the case goes back to the Supreme Court.

The Perez case concerns money allocated to the Interior Ministry in early 1989 for unspecified “security use.” Perez is accused of exchanging the money for dollars at a favorable rate and using the resulting $17.2 million to pay for his 1988 presidential campaign. He denies that, saying the money went for “national security and defense” outside the country. But he refuses to provide an accounting.

His supporters also note that such “slush funds” are common in Venezuela and are designed to be used at officials’ discretion.

Even if impeachment occurred, there is no guarantee that Perez would leave office immediately. Similar charges were filed last year by Causa R, a leftist political party, but were dismissed.

Some legal experts say that unless Escovar has new evidence, there is little chance of a conviction, given the disruption that would follow. Perez also is expected to try to drag out proceedings until December’s national elections are so close that the process would be moot.

In the minds of several experts and diplomats, a moot outcome is too rational to be real in a country that seems to prize disruption and instability. There are efforts, for example, by Perez’s own party to advance election day from December to September or to force the president to resign.

“There are too many people with their own agendas who think they can come out on top if they can push this thing,” one senior foreign ambassador said.

The diplomat pointed to the ambiguous positions taken by several of the dozen or so politicians who are considering running for president. He noted, for example that Nelson Socorro, Perez’s solicitor general and leading backer, resigned last month, saying there was “an obvious problem” in the manner the president had used the questioned funds.

No matter how the impeachment process ends, the diplomat said, “a coup remains a definite possibility.”

In effect, said a diplomat, “no one thinks of what’s best for the country, or that there is something counterproductive to democracy in trying to overthrow an elected president months before he has to leave anyway. It’s as if the political elite sit around and think, ‘What can we do bad tomorrow?’ It is cannibalistic.”

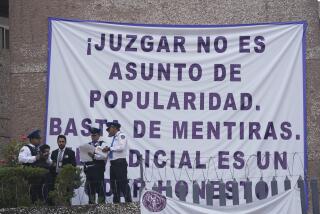

One senator recently told the Miami Herald that “people on the street want an impeachment. There’s a mass hysteria building up.” That is evident on a daily basis. Students leave classes to demonstrate, often resulting in clashes with police that leave dozens of people hurt.

The situation got so bad recently that Defense Minister Ivan Jimenez said he could not guarantee there would not be a military uprising, leading the army’s high command to go on television to deny such a possibility.

All of this has led to a major increase in capital flight as businessmen send money out of the country. One of the contradictory elements in the anti-Perez campaign is the health of the country’s economy. Perez’s plan to free Venezuela of its oil dependency and to open up the economy by moving to a freer market gave the country a 1992 growth rate exceeding 6%, one of the highest of any major nation in the hemisphere.

But the dislocation, caused particularly by the termination of government subsidies of the middle class, has bolstered the bitterness of the people normally most supportive of democracy.

“You have to remember that the middle class here was spoiled,” one political analyst said. “To them, middle class means cheap energy, low taxes, low prices for their purchases and a lifestyle only the rich enjoy elsewhere.”

When asked what he thought would finally happen, one diplomat said he had no way of telling. “The normal patterns of behavior no longer apply here. My country doesn’t need an ambassador here, it needs a psychiatrist.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.