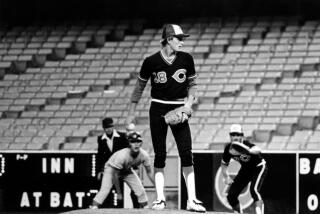

A Merciful End : Ryan Is Finally Retiring, and It’s a Good Thing Because This Fan’s Obsession With the Pitcher Is Taking Its Toll

I’m glad Nolan Ryan is retiring this year after 27 seasons because, frankly, I needto get on with my life.

Childhood heroes are not supposed to stalk us into our mid-30s but, alas, there is Ryan, the ageless wonder, who insists on holding hostage the last link to my adolescence. By all rights, we should have cut this cord at least 10 years ago when Ryan was throwing 95 and pushing 36.

But no, he had to keep on pitching, and pitching, and pitching, and there was nothing I could do but go along for the ride.

Embarrassing, really, that a man with a 30-year mortgage and bunions should set his life to a five-day rotation during baseball season; that he would know without research that Ryan owns the 18th-lowest earned-run average in history; that he would remember May 9, 1979, as the day Ryan’s 7-year-old son, Reid, was nearly killed after being struck by an automobile.

I pledge no such allegiance to any other player and profess I would not even follow baseball closely if not for the fact a 46-year-old freak of science, whom I have been tracking since I was 13 and spackled in Clearasil, is still pitching.

OK, I worshiped Jerry West as a kid, too, but at least he moved on to the pantheon at a respectable age.

Once you latch onto the Ryan Express, there is no turning back. I took a blood-oath at the School of Ryantology long before it was fashionable, long before he became a folk hero and--God knows--long before he became a cinch to make the Hall of Fame.

I am not altogether proud to say that I negotiated his name onto the birth certificate of our first-born, Daniel Ryan, or that I even considered the name Alvin (Ryan’s hometown in Texas), for our second boy.

But such is the illness. If there were a Betty Ford Center for Ryan addicts, I’d be raking leaves on weekends, bribing the guards for box score updates.

Being a Ryan fan isn’t what it’s cracked up to be, nor what it used to be. Now, you have to stand in line. When Ryan pitched for the Angels for eight seasons in the 1970s, we had him to ourselves.

About the time the Angels fell off the pace in the American League West each season, usually June 1, a teen-ager could blow out of his screen door in North Orange County at 7:05, tear south on the Orange Freeway, never hit the brakes, buy a box seat at 7:25 and catch the last verse of the national anthem.

Ryan was the greatest thing we’d ever seen, a hard-luck, one-man marvel on a team of has-beens and sore-arms.

The record will show he was sent to us from the New York Mets on Dec. 10, 1971, along with three others in exchange for Angel shortstop Jim Fregosi.

To us, he was heaven-sent.

We would have paid just to hear the sound of his fastball popping a catcher’s mitt.

We knew he was wild. We knew he was different. We knew our lives would never be the same.

There were more logical idols to consider.

To the east, one could bow to the immaculate Jim Palmer, Mr. Pitcher-Perfect, who never allowed a hair be out of place or, to my memory, a base on balls.

Ryan fans would grow to despise Mr. Fruit of the Loom, or whatever he wore, not only for depriving Ryan of the Cy Young Award in 1973 (I have considered a doctoral thesis on this subject) or making inflammatory comments about our man afterward--”All Ryan does is go for strikeouts”--but for pitching most of his career for a pennant contender.

As Palmer was racking up Cy Young awards faster than Ryan was losing ninth-inning no-hitters, we wondered if it mattered that Gentleman Jim was serving up grounders to infielders Brooks Robinson and Mark Belanger while Ryan’s fortunes were tied to “Dirty Al” Gallagher at third base and Orlando Ramirez at shortstop.

Palmer never won 20 games for a last-place team; Ryan did.

And I will admit to hoisting a small toast when Ryan passed Palmer--oh it must have been years ago--on the all-time victory list.

Being a Ryan fan is agony and ecstasy. There are the 319 wins and the seven no-hitters to savor, plus all the strikeouts, but also 287 losses.

Every loss has been a punch to the stomach because, as Ryanaholics will attest, he could have easily won 100 of those games had he pitched for better teams.

I will sign an affidavit in any court testifying that I have personally witnessed 50 games he flat-out should have won. In history, only Walter Johnson has lost more 1-0 games than Ryan.

When Ryan-baiters try to get my goat about the losses, I feign indifference. “You have to be great to lose that many games,” I’ll say.

Cy Young lost 300.

Listen up, Ryan-bashers. Baseball is a team sport. If Ryan were a tennis player and had a .500 record, that’s another story.

But baseball is an inexact science, a sport in which a pitcher has only limited control over the outcome.

This would explain how the great Bob Feller could have 100 more wins than losses in his career with an ERA of 3.25, while Ryan is called a .500 pitcher with a lower career ERA, 3.17 (it was 3.15 until last season).

I argue that ERA is the only true measurement of a starting pitcher, and Ryan stacks up with the best.

I warned you this was a sickness. Don’t get me started on Ryan vs. Sandy Koufax.

Nothing came easily for Ryan, which was part of the attraction.

We struggled with him through his bouts of brilliance and wildness.

With the Angels, it was not uncommon for Ryan to walk the bases loaded and then strike out the side.

To us, this was a good thing.

Before cable television connected him to the provincial eastern media establishment, Ryan was our little Pacific Daylight Time secret, the only reason to plunk down your paper-route money on the Angels.

On the marquee outside the stadium, the Angels used to promote games as Nolan Ryan vs. the Cleveland Indians.

Because that’s what it was.

The attraction to Ryan off the field was much the same as it is today. While we constantly made excuses and cursed his teammates, Ryan never did. He was a class act.

He would lose a game, 2-1, on some triple-A reject’s two-run error, and then blame himself. “I shoulda struck the guy out,” Ryan would drawl.

Meanwhile, Ryan’s supporting cast drove us up the foul pole. It didn’t help that the guys backing Ryan in the bullpen were dubbed “the Arson Squad.”

Ryan never pitched for a team with a Murderer’s Row. We would have settled for second-degree manslaughter’s row.

One year, the Angels were known as “the Running Rabbits.”

And people wondered why he tried to strike everyone out.

Why? Because it was his best defense.

And because he could.

I remember one of Ryan’s season-opening starts in the mid-’70s, against the Oakland A’s. He fanned something like 11 batters in six innings and was clinging to a one-run lead. After two batters got aboard in the seventh, the manager pulled him because he feared Ryan was tiring.

The reliever, Paul Hartzell (I know where you live), gave up a two-run double, and Ryan was tagged with the loss.

A friend and I ran out of Anaheim Stadium, literally screaming. We spilled aimlessly into the parking lot. It took us an hour to find our car.

As much as the wins and strikeouts, this is what it means to be a Ryan fan.

The problem is, 20 years later, I’m still running out of stadiums, screaming.

Why couldn’t Ryan have been a mortal with normal bone tissue?

As hard as he threw, we figured he’d blow his arm out before his 30th birthday (See Koufax, S.; arthritis).

Why did he put us through this?

Sure, we will treasure those misty-eyed moments--no-hitters No. 6 and 7, 300 wins, 5,000 strikeouts.

Ryan fans are thankful our man finally got his due, that we will not have to mail cut-and-paste death-threats to Hall of Fame voters.

We are glad you all discovered this genuine American hero. So tell us something we didn’t know.

But we have also known much pain and suffering. There was 1987, the year Ryan won his second ERA title, the strikeout crown and finished 8-16.

I remember the night he struck out his 5,000th batter, Rickey Henderson, not because of the moment, but because he lost the game, 2-0.

I don’t have enough stomach lining to follow Ryan much longer.

I cannot jab any more pins into a likeness of Buzzie Bavasi, the former Angel general manager who let Ryan escape as a free agent after the 1979 season.

I can’t take another Ryan hamstring pull.

I want my fifth days back.

I understand it is ridiculous for a grown man to have come to memorize his gym locker combination because one of the digits is 30, Ryan’s number with the Angels.

It is disturbing that I can now tap into the Sports Ticker on nights Ryan is pitching and follow the course of his games.

It is not normal that friends call me at home with Ryan no-hitter watches--”Ryan’s allowed no hits through six”--as if I didn’t know.

I am tired of being bound and gagged to every Ryan start.

I want the freedom to, in case of family emergency, turn away from a game before Ryan has surrendered a hit.

This superstition dates to Sept. 26, 1981, when Ryan was pitching for Houston against the Dodgers.

I was in Tucson to cover a football game between Cal State Fullerton and Arizona. Another reporter and I were about to leave the hotel to attend a luncheon when I turned on the game.

“I’m not leaving until Ryan gives up a hit,” I said.

We bagged the luncheon, ordered room-service pizza and watched the completion of Ryan’s record fifth no-hitter.

But enough is enough.

I’m tired of dragging myself to various Ryan tributes whenever he rolls into Anaheim now with the Texas Rangers, only to fight my way through throngs of Ryan worshipers.

If all these people had shown up when he pitched for the Angels, maybe Gene Autry would have coughed up the money to keep him.

As it is, a man with a 401K plan should not, as I did last year, call the press box at Comiskey Park, posing as an anonymous fan, to settle an argument between television announcers about whether Ryan had ever thrown more than 200 pitches in a game.

“Uh hum, hello, this is a fan calling. Ryan once threw 241 pitches in a game when he pitched with the Angels . . . . Click.”

And they reported it on the air!

It isn’t right that I still think the best commercial ever made was the one Ryan’s wife, Ruth, made for Mazzola corn oil.

I am tired of monitoring the lives of the Ryan children--Wendy, Reid, Reese. I’ve got kids of my own to worry about.

I am too old to be wrestling Ryan literature away from 13-year-old kids down at the local bookstore--”Listen punk, I knew him before you were born!”

I am ashamed to still be clipping Ryan milestones from the morning paper and pinning them up on my den wall next to my college diploma.

Don’t get the wrong idea. This isn’t Mark David Chapman talking here.

As a kid, I never hung around after games for Ryan’s autograph. I never collected his baseball cards.

I met Ryan once, in 1985, for the purposes of an article I was writing about the pitcher’s longevity.

He was 38 then.

I never wanted to meet Ryan.

The fear is that the idol, in the flesh, would somehow let you down, that he can never live up to expectations. I was sweating bullets when I approached him, but Ryan lived up to his image as a gracious, Texas hick.

Unlike Pete Rose or Ben Johnson or Steve Garvey, we are relieved that Ryan is one idol who has not besmirched his good name.

So thank you, Nolan Ryan. And curse you, too, for the memories and the ulcers.

I’m glad you hung around long enough to tip your cap one last time around the league.

I’m happier that you’re finally hanging up the six-shooter, though.

I can’t go on like this. As it is, I have six years to gather my strength for the trip to Cooperstown, N.Y.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.