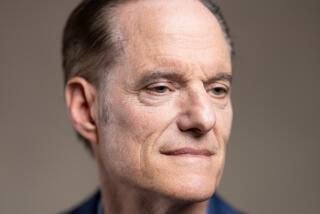

Pastor Finds a Corporate Calling in $3-Billion Health Care Organization : Business: The Rev. Karl Kniseley II offers a voice for medical ethics and values at Burbankâs UniHealth America Foundation.

Donât get the wrong idea.

When the Rev. Karl Kniseley II calls himself the âcorporate conscienceâ of a $3-billion health care organization, he doesnât mean heâs the kind of guy who strides down hospital corridors preaching the moral decrepitude of American techno-medicine.

Instead, his assignment is to see that Burbank-based UniHealth Americaâs 13,000 employees, 2,000 volunteers and 5,000 staff physicians maintain a lively appreciation for such knotty moral-medical problems as abortion, euthanasia, the right to refuse treatment and the rationing of high-cost services.

A former parish pastor for 20 years at Lutheran churches from rural California to downtown Los Angeles, he has a âcalling to special serviceâ from the church to conduct his ministry in the glass and marble environment of the corporate headquarters.

Kniseley is president of the UniHealth America Foundation, the voice of medical ethics and values for UniHealth. The health care system operates nonprofit hospitals and clinics, including Valley Hospital Medical Center, Northridge Hospital Medical Center and Glendale Memorial Hospital and Health Center.

It is a delicate mission. With an annual budget of $200,000 and no formal power within the corporation, the Glendale resident relies mainly on the gentle-toned persuasion of the pulpit.

âIâm not out there charging, leading the troops,â Kniseley said. âOur mission is education, to help us understand the values that are in conflict. I would describe the concept as being a kind of salt in the stew, to bring out the flavor.â

In seven years on the job, Kniseley has helped build up bioethics committees at the systemâs hospitals, set up seminars on ethics, promoted hospice programs and fought to get a paid chaplain on every hospital staff. His latest project is to involve his corporation in the inoculation of inner-city youth.

A short, roundish man of 52 with a coy Tim Conway smile, Kniseley is the kind of guy who joins every committee, gets to every meeting on time and makes his points by posing questions rather than delivering sermons.

The questions are many.

âWhat kind of health care we will have and who can get services?â he asks. âDo we want to make it so that a person never dies alone? That they might have a pump to give themselves medication when they feel pain? That we donât have a 90-year-old person beaten on the chest when their heart stops?â

Colleagues regard Kniseley with warmth.

âHeâs a lovely man,â said Dr. Melvin H. Kirschner, chairman of the bioethics committee at Valley Hospital in Van Nuys. âHe comes up with some wonderful things.â

Even close associates have a hard time saying how Kniseley might answer some of the questions he poses. His own theology is not the point, Kniseley says. To get people talking about ethical issues is.

âIâm not in the business of being a moral regulator. People have to do their own regulating,â Kniseley said. âMy role is to shine a light on the issues through education.â

Kniseleyâs interest in health care arose from church experience.

A graduate of Hoover High School in Glendale and UCLA, Kniseley followed a strong family tradition in entering the seminary in 1962. His father and grandfather were Lutheran ministers, and so is his brother. His pastoral life took him first to Sanger, Calif., back to Glendale, then to San Jose and finally Los Angeles.

âAs a parish pastor, I was in and out of hospitals and rest homes, with families at the point of death,â Kniseley said.

He wasnât always happy with what he saw. âBetween what we said as a people we wanted to do and where we were, there was a major gap. I felt as a part of my life work, I wanted to make a contribution there. And still do.â

A nearly fatal illness in 1984 catalyzed Kniseleyâs career perspective.

As he lay in the hospital two weeks, he said: âI realized my ministry at the church was essentially finished. It wasnât enough to be a parish pastor.â

Seeking insight into the political system, Kniseley enrolled at Loyola Law School, but stopped short of a degree when, in 1986, Lutheran Hospital Society board chairman Sam Tibbetts steered him into corporate work.

âI felt that we needed a foundation that would devote itself to ethics, to values, to our chaplaincy program, to relationships with the church, also relationships with the community,â Tibbetts said.

Kniseley, then senior pastor at the First Lutheran Church of Los Angeles and a board member of Lutheran Hospitals, helped set up the foundation, and was named its president.

Two years later, the job transferred to the secular UniHealth America, formed by the merger of Lutheran Hospital Society and HealthWest Foundation.

As foundation president, Kniseley has focused attention on the UniHealthâs bioethics committees. In theory, these groups, consisting of doctors and administrators, are charged with helping work out hospital policy on such issues as disconnecting life support and providing a non-binding forum for discussion of individual cases.

Kniseley found UniHealthâs committees moribund in some cases, nonexistent in others. He began lobbying to beef up the staffing of the existing committees and to encourage the formation of new ones. So far, seven are functioning at the systemâs 12 hospitals. Kniseley sits on each. He also spurred the formation of UniHealthâs Bioethics Institute, a systemwide committee which supports and coordinates those at the hospitals.

To keep employees and staff physicians informed on new trends and legislation in medical ethics, Kniseley has set up periodic seminars within the hospital. One now being planned will contrast views of all the worldâs religions on the end of life and beginning of life.

The foundation also gives financial support to outside groups such as California Health Decisions, a round-table on health care issues. It annually co-sponsors the national âFrontiers of Healthcare Ethics Conferenceâ with the Pacific Center for Health Policy and Ethics at USC.

This yearâs conference Tuesday will address ethical questions raised by genetic technology, such as genetic screening for untreatable diseases in fetuses and the moral role of the genetic counselor.

Although his position is unusual, Kniseley isnât blazing a new role for the theologian in medical decision-making. Catholic and other denominational hospitals commonly have clergy positions to oversee ethical issues, said Vicki Michel, associate director of Pacific Center for Health Policy and Ethics at USC.

It is rare, however, for a secular institution such as UniHealth to employ a member of the clergy, Michel said.

In the Lutheran church, Kniseley said, he knows of only one other pastor who has been granted special calling to work in nondenominational hospitals. The other is in Chicago.

Lutheran ministers are frequently granted special callings to enter lay work, usually, however, to teach or take executive positions in the church-affiliated ventures such as elderly housing. Pastors who desire secular work are generally given leaves to explore whether they want to remain in the clergy.

However, Bishop Roger Anderson, who sponsored Kniseleyâs case for special calling before the churchâs Senate Council, sees the job as parallel to that of a parish pastor.

âThe connection is he serves as pastor of the church in that setting, giving his own input and witness to that corporation in whatever ways that he can,â Anderson said.

âThis is a lot like what a parish pastor does,â Kniseley added. âYou talk to people privately. They make the decisions. I have people stop me regularly. They say, âWhat do you think?â I tell them. You do not make the decisions for them.â

And if the decision is ever made for him, he said, he would obediently give up his corporate ministry.

âIf this whole thing blew up, Iâd be happy to be a parish pastor again.â

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production â and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.