Giant Icebergs May Pose Threat to Shipping in Alaska : Nature: Chunks the size of several football fields separate from glacier. Scientists fear they could reach the gulf.

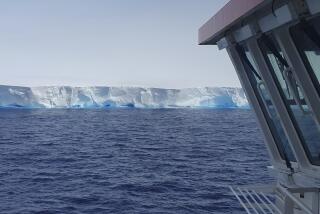

JUNEAU, Alaska â The second-largest glacier in North America has entered a âcatastrophic retreatâ phase, scientists say, and is disgorging giant icebergs that could endanger shipping in the Gulf of Alaska, including tankers traveling to and from the oil port of Valdez.

The largest of the icebergs, some as long as five football fields, currently are trapped inside a lake at the foot of the Bering Glacier and only smaller bergs are able to travel down a shallow outlet to enter the gulf. But scientists fear that a winter storm could breach a narrow sandbar that now blocks the larger bergs and allow these giant chunks of ice to reach the gulf as well.

âThe big concern is that the glacier is less than 60 miles away from Prince William Sound,â and currents would carry the bergs toward the sound, which oil tankers must traverse to reach the port of Valdez, Bruce Molnia, chief of the U.S. Geological Surveyâs international polar programs, said in an interview. âSo a berg that gets caught in the current and survives 48 hours will end up in or near the shipping lanes.â

The Bering Glacier is the longest glacier in North America, reaching 125 miles back into the Chugach Mountains on Alaskaâs south central coast and covering an area of 2,300 square miles. It is only slightly smaller in total mass than the largest glacier on the continent, the Malaspina, which lies just to the east of the Bering.

Both glaciers are in an extremely remote area, so icebergs that break off from the Bering can travel undetected for days through waters that are traversed by fishing vessels and commercial ships. The Coast Guard attempts to track most major bergs, but if the number and frequency increases dramatically, that would make the task far more difficult, one official said.

Molnia said the problems posed by the Bering are not going to go away soon. Scientists believe that because the deep lake at its base extends far underneath it, it will continue to calve off large icebergs for 50 to 100 years in a process that is not likely to end until the giant glacier has retreated about 30 miles back into the mountains. At least a third of the glacier is expected to break off into icebergs that are now trapped by a narrow sliver of sand that appears to be eroding dramatically.

The sandbar, which was deposited along the tidelands by the glacier when it sat on the edge of the gulf earlier this century, is only about 1 1/2 miles wide. The Seal River passes through the sandbar and connects the gulf with Vitus Lake, one of the largest freshwater lakes in Alaska, which was created by the retreat of the glacier.

Flat icebergs that do not have a deep draft are able to make it down the Seal River and into the gulf, and they tend to melt or break up before posing too much of a problem for ships. But their numbers are growing dramatically as the glacier accelerates its calving.

Molnia, who along with other U.S. Geological Survey scientists has been studying the Bering for several years now, said the rate of calving has increased dramatically in the past couple of years.

In mid-July, he said, the 15-mile-long lake was filled with icebergs trying to get down the river and out into the gulf. âIt was just wall to wall with icebergs,â he said.

Many bergs measuring up to an eighth of a mile in length are already getting out into the gulf. For a while this summer Molniaâs team kept track of the number of bergs reaching the gulf. The number ranged from one an hour to a peak of 806 in one hour on July 15.

Those icebergs are not large enough to pose much of a danger in Prince William Sound, but they could demolish a fishing boat in the heavily traveled waters between the communities of Cordova and Yakutat, Molnia said.

Molniaâs team established eight stations along the beach to measure the rate of erosion, and the results this year have not been encouraging. Each station includes a series of stakes in the beach at various distances from the high tide line.

âWe lost two stations completely,â so in two different areas, more than 120 feet of beach eroded away this year, he said.

Such a high rate of erosion could be accelerated by the fierce winter storms that blow in off the gulf, and Molnia worries that erosion and storms could simply break through the narrow sandbar.

âThe long term concern is that erosion could open a channelâ and allow the larger bergs to move into the gulf and endanger shipping, he said.

The Bering Glacier is not unique among Alaskaâs coastal glaciers in that most are retreating to some degree as the final manifestation of the end of the Little Ice Age, which began about 5,500 years ago and lasted in some areas until the last century. The glaciers grew during that period of increased precipitation, and most maintained their maximum size until the last few hundred years. Some, like the Bering, held their maximum position until less than a century ago, and then began rapid retreats.

The Bering Glacier is different from most, however, because as it retreated it left a great lake in the basin it had once occupied. That lake is up to 600 feet deep near the foot of the glacier, and seismic soundings indicate that a deep basin beneath the glacier goes back for about 30 miles. Thus there is nothing to stop the glacier from calving off huge icebergs, and the lake will continue to extend inland as the glacier recedes.

Alaskaâs Iceberg Alley

The Bering Glacier is unleashing huge icebergs into Vitus Lake, Only small icebergs make it down Seal River to the gulf, but experts fear a sandbar will open up and allow the giant bergs to reach shipping lanes.

North Americaâs second--biggest glacier

The glacier covers 2,300 square miles. As shown below, if it were droped off the coast of Southern California, it would reach from Santa Monica to south of San Diego, and would bridge the space between Venice Beach and Catalina Island.

Anatomy of the Threat

1. The Bering Glacier is different than most because as it retreated it left a great lake (Vitus Lake) in the basin it had once occupied. 2. The lake is up to 600 feet deep near the foot of the glacier, and seismic soundings indicate that a deep basin beneath the glacier goes back for about 30 miles. 3. The glacier could continue to calve off large icebergs for 50 to 100 years as it retreats the length of the basin.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.