Home-grown suds helping to brew local pride : Handcrafted beer industry thrives with several quality brands.

SEATTLE — Flying high over the gloomy face of recession, America’s handcrafted beer industry is expanding at 30% or 40% or even 50% a year--reclaiming foreign inroads in the U.S. market by offering that most elusive of domestic commodities: old-fashioned quality.

And brewers of handmade beers are contributing, if only a little, to restoring a sense of community by producing local ales and lagers in the manner of the past: something special for a town, something that is its alone.

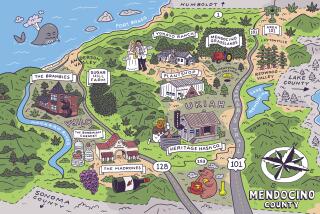

The Northwest and Northern California are the cradle of this renaissance in quality, small-scale brewing.

The trend caught on a dozen years ago in San Francisco (Anchor Steam) and Chico (Sierra Nevada). But it has gained momentum and broader popularity as it moved north.

Northern California may have more micro-breweries, but Portland and Seattle consider themselves America’s new Bavaria. Beers of distinction have penetrated the everyday culture and are no longer just a novelty.

Here, people do not enter a saloon and say “gimme a beer” any more than they would tell a waiter to “gimme food.”

Here, beers are apt to range in color from amber to deep red and on to smoky dark brown, not just uniform pale golds. Here, flavors run from creamy rich to fruit tangy. Here, you have your ales and your lagers and your porters and your stouts and even your malted wheat beers that are served with a slice of lemon. Here, brewers celebrate the winter by bringing forth treasured once-a-year recipes designed to say happy holidays, and they gather several times a year for other brew festivals.

Depending on where in the Northwest you live, your local pub may pour Red Hook Ballard Bitter or Bridgeport Blue Heron or Widmer Weizen or Pyramid Pale Ale or Hale’s Wee Heavy or any of more than 100 others.

Jack Erickson’s 1991 book, “Brewery Adventures,” counts 99 breweries and brew pubs, where beer is made and consumed on the premises, in the region from San Francisco to the Canadian border. Each is apt to produce several different beers.

Why here in the Northwest?

One reason is proud parochialism. Cities such as Portland and Seattle not only welcome but thirst for things that will distinguish them from other places.

Breweries do that nicely.

After all, up until Prohibition, American breweries were local operations just like the hardware store and bakery. Only later did giant firms emerge to dominate the market with beverages that led generations of Americans to mistakenly believe beer is a drink with only subtle variety.

Today, the notion of handcrafted beer stands in curious defiance of some of the strongest trends in the U.S. food and beverage industry--national marketing, franchising uniformity and advertising.

Industrial brewers spend millions promoting their light, or so-called dry, beers and regular beers of absolutely consistent composition. Craft brewers are just the opposite, offering richer, more complex beers--and sometimes widely variable beers--using little if any advertising.

But craft brewers also appeal to the growing interest in quality and freshness.

Good handcrafted brewers are fastidious about purity and use only four ingredients: water, hops, malt and yeast. Many believe the secret of good handcrafted beer is the ingredients--plus one more thing.

“Freshness--it’s everything,” says Vince Cottone, beer columnist for the Seattle Post-Intelligencer. “People are rediscovering the tastes and quality of fresh foods. That is one important reason these local beers are prospering.”

Unlike wine, beer does not age well. It is a fragile drink that can be spoiled by temperature, time or rough handling.

Many beer fanciers are known to wonder why German beer tastes so much better in Bavaria or British beer in a London pub. Imported to America, these beers invariably seem to lose their zest.

Freshness is the chief reason given by American brew masters, although they credit foreign beers with lifting the sophistication of U.S. beer consumers.

But those imported beers, about 6% of the U.S. market, are now the targets of the new American craft brewers.

“So many times in our society we must live with a standardized industrial product until foreigners come along and offer us something better,” says Paul Shipman, president of Red Hook, the largest of the Northwest craft breweries.

“The world I’m working for . . . is one in which small, specialty breweries can serve the appetite for alternatives to the big national beers. Then there will be no need for any importation of beer, except maybe for those few that are completely unique.”

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.