A Researcher Becomes Promoter

For some research scientists, the reward is simply to âmake new science,â to find some basic, esoteric discovery that may have no immediate application but will result in a published scientific paper and serve to feed the imaginations of others.

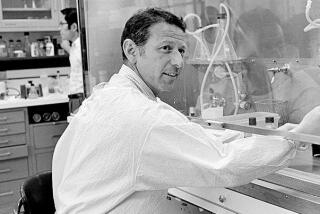

Others, like Dr. Harry Gruber, are driven to take their discovery from the lab to the bedside, to develop their notions into something commercial and marketable and beneficial to society.

Gruber left the research ranks of UC San Diego to develop a drug that may save the lives of heart-attack and stroke victims. If successful, he may be the first to tap a market estimated at $100 million a year.

To achieve this all-consuming goal, Gruber absorbs a continuing personal toll. He misses most family dinners and is in no position to commit himself as an adult volunteer for his childrenâs Saturday sports.

Gruber, 38, lives in Carmel Valley with his wife and their three children, 11, 9 and 4. What does he do for fun? âMy work is my hobby,â he said. âI work close to 100 hours a week--almost every Saturday and Sunday, at my desk, on the phone, in meetings. Lots of fund raising and interactions with scientists.â

Is he a workaholic?

âNo. Thatâs someone who doesnât like what theyâre doing. Itâs an illness. What I do, I have to do. I donât work to avoid something. Iâve never missed (celebrating a childâs) birthday,â he said.

âIf thereâs resentment at home, itâs that I never coached a team. I canât commit Iâll always be there, every Saturday morning.â

Gruber figures that, out of seven dinners a week, heâs home for one.

âBut my kids, I think, are proud of what Iâm doing.â

Gruber, a medical doctor, embarked on his scientific project--one with grand commercial potential--after joining the staff of UCSDâs School of Medicine in 1977. There he wanted to conduct research in biochemical genetics that âwould lead to something practical.â

In 1980, he began specifically focusing on a hormone called adenosine, a kind of molecular first aid kit that prevents injury to tissue after a stroke, heart attack or arthritis grips the body.

In 1984, UCSD filed for a patent on his breakthroughs, and Gruber began his search for a local âcorporate partnerâ to help him commercialize his invention.

âIt was a learning process for me to realize that, in order to see my project through, Iâd have to go to private industry and not stay at the university,â he said.

âI recognized that, for something to be commercialized, or to at least undergo extensive development, it takes a product champion--someone who is willing to push that concept to its limits. Itâs the inventor--in this case, me--who becomes that champion. I can either hope someone else will push it along on my behalf, or push it myself.â

Since in-house scientists at commercial biotech firms are usually preoccupied with their own notions and arenât anxious to drop their agenda for an outsiderâs idea, Gruber decided to form his own company. Itâs a traditional scenario in the brand-new world of biotech start-up firms.

Through a series of fortuitous contacts with local investors, Gruber in 1986 rounded up enough money from venture capitalists to found his company, Gensia. While still putting in his 40-hour workweek at UCSD, he got university permission to do consulting work for Gensia.

But the company couldnât yet do anything.

It âdidnât have the technology yet (to begin the commercial development of the breakthroughs) because UCSD still had the patent,â Gruber said. âAnd they said they wouldnât license the patent to a company that had no real assets. And the venture capitalists wouldnât put money into a company that didnât have any technology to call its own.â

It was a classic Catch-22.

So Gruber sought out existing companies to buy UCSDâs--his--technology. Not to his surprise, there were no bidders other than Gensia, which existed only on paper. Finally, UCSD agreed to license the technology.

âIt was sort of a leap of faith by the university,â Gruber said, faith that Gensia would be able to develop the technology and, eventually, generate royalties for the university.

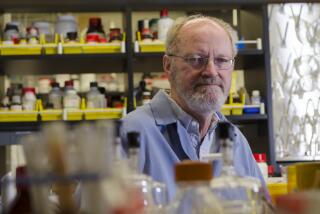

With the technology in its pocket, Gensia locked up $4.6 million in venture capital. In June, 1987, it hired David Hale--whom Gruber had been meeting with for advice on how to start Gensia--as its chief executive officer.

In 1988, Gruber left UCSD and became vice president of research at Gensia.

âI had a lot of fear, leaving the university, but it was clearly the right thing to do,â he said. âI had grants and contracts I had to leave behind. The stress of dealing with potential jealousies of other people was difficult. But I felt that, if Gensia was going to succeed, it needed me.â

Today, Gensia has raised $69 million in capital and has 200 employees. Gruberâs drug is in clinical trials and may be on the market in 1994, with a potential market of $100 million a year.

The drug is intended for people at risk of heart attack--including those undergoing heart surgery--or for people who have had strokes. When tissue is denied blood--such as after a stroke or heart attack--it dies and creates scar tissue, which, in turn, further reduces the flow of blood to other places in the body. Gruberâs drug would increase the production of the hormone adenosine, which helps prevent the formation of scar tissue.

âThese are exciting times, but I tend to worry,â Gruber said. âThatâs why I work so hard. I always think of the next hurdle, rather than the one I just jumped.â