Fountain Valley Man Guilty in Rape Spree : Crime: He is convicted on 34 of 38 charges related to a series of sexual assaults and burglaries, including separate attacks on one woman. He could be sentenced to more than 150 years in prison.

SANTA ANA — A Fountain Valley man was found guilty Tuesday of 34 out of 38 charges related to a series of sexual attacks and burglaries in the Huntington Beach-Fountain Valley area, including the rape of a woman twice.

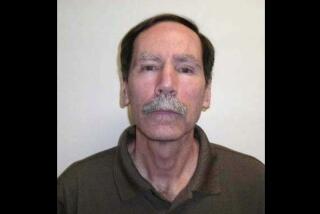

Robin Scott Dasenbrock, 26, whose attorney conceded at the beginning of the trial that his client was guilty of most of the crimes, could face more than 150 years in prison when sentenced by Superior Court Judge Robert R. Fitzgerald on Jan. 11.

In addition to the 34 counts, Dasenbrock had already pleaded guilty to five other assault and burglary counts.

Each of his seven rape victims lived in first-floor apartments, which he usually entered by breaking through a window. His fingerprints were left at the scene of more than half the attacks.

“He didn’t cover his tracks too well,” said David Brodeur of Anaheim, the jury foreman.

The jurors, who deliberated four days, found Dasenbrock not guilty on three counts of assault with intent to commit rape and one count of burglary. Prosecutors conceded that those were the charges in which evidence was the weakest and eyewitness identification may have been tainted when Dasenbrock’s picture appeared in a community newspaper before the victims could see him in a police lineup.

“None of those counts would have had an effect on the sentence,” said Deputy Dist. Atty. Mike Koski. “It shows the jurors were conscientious about what they were doing.”

Dasenbrock was found guilty on all sexual offenses related to the eight rapes, which included one woman raped twice in the same Fountain Valley apartment complex about a year apart. The woman moved out the week after the second rape.

Jurors had sat transfixed as she testified that during the second rape, Dasenbrock had taunted her about the first attack. “ ‘Remember last time, when I had to wait for your boyfriend to leave?’ ” she testified he told her.

In each of the counts in which Dasenbrock was convicted, he was either identified by the victims in a police lineup or in court, or he had left fingerprints in their apartments.

Dasenbrock was living in a Fountain Valley apartment complex near Edinger Avenue, where many of the assaults and rapes had occurred. He was arrested in April, 1987, after he was spotted crouched in some bushes outside a woman’s apartment in Fountain Valley. It was after his arrest that police were able to match previously unidentified fingerprints left at many of the crime scenes.

His attorney, James S. Odriozola, argued to jurors that in some of the attacks, it was impossible to tell when Dasenbrock, an unemployed warehouse worker, had left his prints. Odriozola also tried to show through an identification expert that some of the victims might have been too traumatized during the attacks to properly identify their assailant. But several jurors pointed out that whenever they had a question on identification, the fingerprint evidence usually tipped the scales in favor of a guilty verdict.

Dasenbrock, who is slight of build, took copious notes as the court clerk read the lengthy verdict forms.

“I wouldn’t want him back out in society,” said Brodeur, the jury foreman. “It’s a little scary, really. He looks like . . . he looks like me. He just looks like an average guy.”

Dasenbrock threatened most of his victims either by running a knife up and down their backs or telling them he had a knife. Jurors issued findings that Dasenbrock used a knife in 12 of the 34 counts, which will be a significant factor in sentencing.

Dasenbrock did not testify at his monthlong trial.

None of the victims was in court when the verdicts were read. But prosecutor Koski spent much of the afternoon on the telephone informing them what happened.

Brodeur said he was proud of most of the jurors for judging the evidence objectively without allowing the victims’ tragedies to overwhelm them.

“There were a few occasions when we got off onto philosophy or psychology, and I’d have to get them back on track,” he said.

Brodeur said the jurors took so many days, despite the defense concession on many of the counts, primarily because it was difficult to keep all the counts straight.

“We finally had to assign one juror as the clerk just to keep everything in order,” he said.

One woman crying in court got the attention of news photographers. She turned out to be one of the investigators on the case.

“She’d been with this for five years,” said one of her fellow investigators. “It was a tense moment.”

Koski said he would have a recommendation for the court on a sentence before the sentencing hearing.

“With the magnitude of these crimes and the number of victims, you can be sure it’s going to be a very high number,” Koski said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

![[20060326 (LA/A20) -- STATING THE CASE: Marchers organized by unions, religious organizations and immigrants rights groups carry signs and chant in downtown L.A. "People are really upset that all the work they do, everything that they give to this nation, is ignored," said Angelica Salas of the Coalition of Humane Immigrant Rights. -- PHOTOGRAPHER: Photographs by Gina Ferazzi The Los Angeles Times] *** [Ferazzi, Gina -- - 109170.ME.0325.rights.12.GMF- Gina Ferazzi/Los Angeles Times - Thousands of protesters march to city hall in downtown Los Angeles Saturday, March 25, 2006. They are protesting against House-passed HR 4437, an anti-immigration bill that opponents say will criminalize millions of immigrant families and anyone who comes into contact with them.]](https://ca-times.brightspotcdn.com/dims4/default/34f403d/2147483647/strip/true/crop/1983x1322+109+0/resize/840x560!/quality/75/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fcalifornia-times-brightspot.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fzbk%2Fdamlat_images%2FLA%2FLA_PHOTO_ARCHIVE%2FSDOCS%2854%29%2Fkx3lslnc.JPG)