Foothill Looks for Firms That Look for Loans : Agoura Hills: The strategy is essentially investments in businesses that most banks think arenât worth the risk.

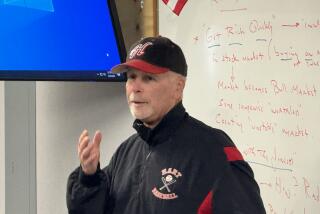

At 7 a.m. Don L. Gevirtz was already trolling for business at a recent breakfast meeting, telling dozens of executives from little-known local companies something most of them probably knew: how tough it is to get money for their businesses these days, when tight credit and a looming recession have cut off many of the usual sources.

Can you still get a bank loan? Gevirtz said, âThe line is forming around the block.â What about selling stock to the public? Itâs âvery difficultâ with todayâs uneasy stock market, he said. How about the federal Small Business Administration? Itâs âa huge boondoggle that should be eliminated,â Gevirtz said.

So whoâs left? Why, asset-based lenders like The Foothill Group Inc., the Agoura Hills company where Gevirtz is chairman and which he helped found in 1969.

Asset-based lending is jargon for companies like Foothill that make higher-risk loans to new or troubled companies. The loans are secured with collateral that can be easily converted to cash--such as accounts receivable, or money a company is owed for merchandise or services. The interest rates are three or four points above the best bank rates to compensate for the risk.

Gevirtz said the same conditions that make it hard for companies to borrow are good news for asset-based lenders. Foothill, he argues, can thrive in tough times because banks get choosy, forcing some companies--that normally would go elsewhere--to pick Foothill.

But these days, investors arenât rushing to bet on Foothillâs stock. They are worried about losses from Foothillâs relatively small junk bond investments, the main factor behind the companyâs $4-million second-quarter loss. In fact, Foothillâs stock closed Monday at $3.50 per share after trading as high as $7.25 on the New York Stock Exchange earlier this year.

But Gevirtz says heâs not worried about the stock price. Heâs concentrating on Foothillâs strategy for benefiting from a troubled economy. âEverything weâve been doing has been aimed at a recessionary environment like we think we are just about in,â Gevirtz said.

Foothillâs current strategy is essentially to get out of the junk bond business by slowly selling off the whole portfolio, and to focus on its strength: investments in companies that most banks think arenât worth the risk.

Whether the strategy is recession-proof remains to be seen. Foothill did well in the recession of 1974-75. But in the recession of the early 1980s Foothill lost $18 million over two years after it invested far too heavily in the oil patch, then got clobbered when the oil glut hit.

But itâs not doubt about Foothillâs ability to make the best of tough times that has sent Foothillâs stock spiraling. Investors are clearly focused on the companyâs modest portfolio of junk bonds, according to Seymour Jacobs, an analyst with Mabon, Nugent in New York. Jacobs isnât worried though. âI think the stock market has overreacted to damage in the (junk bond) portfolio,â Jacobs said.

Foothill all but stopped buying junk bonds several years ago. The reasons are fairly plain. Junk bonds, which are riskier bonds that pay high interest rates, can be a dangerous asset during a slowdown or recession, when cash-strapped companies are more likely to default. And the market for junk bonds has collapsed in the last year.

But it was not until June 30 that Foothill wrote down the value of its high-yield portfolio (mostly junk bonds) by $9 million to about $39 million. The writedown is recognition that the bonds have lost some value, and that decrease is essentially subtracted from the companyâs revenues.

Due in part to the writedown, Foothill reported a second-quarter loss of $4 million, compared with a $3.2-million profit a year earlier. The loss came on a 52% plunge in Foothillâs quarterly revenue to $13 million from $27 million--a change that also mainly reflected the junk bond writedowns. Since then, Foothill has also sold some of the junk bonds, said John F. Nickoll, Foothillâs president and co-founder.

In addition to taking some riskier assets off the balance sheets, selling the bonds will provide Foothill with cash to help pay off debt.

Despite some stockholdersâ fears, thereâs no sign that other investors in Foothill are worried about the junk bond holdings. Phillip Zahn, analyst with Duff & Phelps Inc., a credit-rating firm in Chicago, said institutional investors bought up $100 million in notes from one of Foothillâs subsidiaries--Foothill Capital--in the first six months of 1990.

But the government may not have been so complacent. Gevirtz and Nickoll said that Foothill and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., which insures deposits at Foothillâs other main subsidiary, Foothill Thrift, agreed that the thrift should write down the junk bonds and sell them off. Neither Gevirtz nor a spokesman for the FDIC would elaborate.

With the junk bond problems left behind, Gevirtz argued, Foothill should be able to concentrate on its main businesses--asset-based lending--where he said there are already signs of good times to come. Analyst Jacobs agreed. âAsset-based lending is really the vast majority of this company,â he said.

Foothill has two main lending subsidiaries. Foothill Thrift & Loan, which has $216 million in assets, is not a savings and loan, although it resembles one in some ways. It makes loans to businesses, secured by real estate and equipment, and accepts consumer deposits at its six retail branches. The thrift is chartered by the state, and its deposits are insured by the federal government.

Meanwhile, Foothill Capital, with $384 million in assets, makes loans to businesses that banks consider too risky. Most of the loans are secured by accounts receivable, and some are secured by a companyâs inventory.

Both subsidiaries should see an increasing demand for their loans, Gevirtz said. Henry K. Jordan, Foothillâs chief financial officer, said Foothillâs backlog of requests for asset-based loans has already doubled since last year. With more prospective borrowers, Foothill can be choosier about the risks it takes.

And Gevirtz said Foothill can protect itself from an economic downturn because of the way its loans are structured. For instance, at Foothill Capital, many of the loans are day-to-day borrowings a customer uses to pay for raw materials it needs to produce its products. The borrowings are quickly paid back, and their size is essentially based on the borrowerâs accounts receivable--the amount of money owed to it by people who buy its products. That way, if a company sells less of its products, Foothill cuts its exposure to the company by lending it less money.

In addition to the two main subsidiaries, Foothillâs Capital Markets Division also manages other investorsâ money in two limited partnerships that invest in troubled companies. The same conditions should help its limited partnerships thrive because as the economy slows, more of the distressed securities and loans the partnerships invest in will be available, Gevirtz claimed.

Among the investments are so-called discounted bank debt, loans banks would like to get off their books because the borrowers are having financial troubles. The banks are willing to sell the loans for less than their face value to get rid of the risk of owning them. Foothill, on the other hand, figures it can make money by buying them at a discount.

Despite the borrowersâ problems, such bank loans are considered a safer investment than junk bonds because bank loans are senior debts and typically the first to get repaid if borrowers go belly up.

Foothill will soon start investing money from a third limited partnership, Foothill Partners, which will only put its money in discounted bank debt.

Gevirtz admitted that Foothill didnât independently get the idea to invest Foothill Partnersâ funds only in discounted bank debt. Originally, the fund was to invest in discounted junk bonds too.

But potential investors forced Foothill to rethink the fundâs investment goals. âWe werenât having much successâ marketing Foothill Partners as a bank debt and junk bond fund, Gevirtz said. âNo, thatâs an overstatement. We werenât having any success.â

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production â and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.