He Put Maryland Racing Back on Track and Took It to the Winnerâs Circle

Death, which waits on no man, since not the time nor the hour is printed on a schedule, took Frank De Francis away before the letter ever arrived. The message was written last Wednesday, mailed the next morning and he died the following afternoon in the Miami Heart Institute. Considering the distance involved, itâs presumed he didnât live long enough for it to be processed and delivered.

It was a personal note, as anyone might write to an ill friend, an attempt to provide a lift, a smile but, mostly, to give him a moment away from the monotony of a hospital routine when a few lines might brighten an otherwise taxing day of looking at the same walls and an unending procession of doctors and nurses monitoring pulse and heartbeat.

De Francis didnât need a letter from a sportswriter in Baltimore to underline what he was able to achieve in putting Maryland racing on his back and carrying it to the winnerâs circle. This was a man of extraordinary intelligence, inspiration and imagination. No individual came close to accomplishing what he was able to do for the health and welfare of the industry.

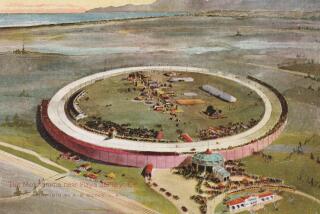

Baltimore and Maryland have never known a promoter like him. He spent millions to improve the Pimlico and Laurel race courses. The tracks were put in first-rate physical condition and the facilities around them, where the public was to be received, had a clean, impeccable, inviting appearance.

The fans and the horsemen received a respect that had never been provided by managements in the past. This, more than anything else, separated De Francis from the rest of the parade. He believed the customer deserved the best that he, as a host, could provide. âThatâs the least we can do,â he once remarked. Yet he did much more.

All sports are in need of people with ideas and leadership. De Francis was a throwback to some of the outstanding promoters, such as George Preston Marshall in football and Bill Veeck and Larry MacPhail in baseball. He went all-out in aggressive pursuit for whatever it was he wanted to accomplish, but he went in totally prepared and immersed in the subject of his discussion.

De Francis conveyed a quality of sincerity and, when he began to talk, either to the governor, the state legislature, a horse owner or a hot-walker, there was little doubt his persuasive ability was going to find him securing the result he sought. Members of the General Assembly, on guard, would see De Francis scheduled for another appearance before a committee.

They knew he wanted something and would brace for his arrival, telling each other they were not going to give in to whatever it was he was intending to request. But, once he started working with the magic of his words, offering logical reasons for supporting the action he proposed and building to an eloquent, effective conclusion, the members would capitulate.

De Francis articulated with an ability that is rare. He convinced the lawmakers racing needed tax relief. Others had voiced the same protestation in the past, ad infinitum, but their cries were never heard. Yet with De Francis, it was different. After his presentation, he went away with a cut from 6 percent to 3 percent in the stateâs betting take and then, only a year later, 1984, got it reduced again to 0.75 percent.

He awarded worthwhile gifts to fans attending the races, which was a change because public perception was the tracks were only in a habit of taking -- and werenât interested in giving. De Francisâ booming oratory won friends and influenced legislators. He had been an international lawyer but also a racetrack enthusiast, owning horses and enjoying the fire and the action so he knew his subject intimately.

King Leatherbury, Laurelâs leading trainer, realizes what De Francis meant to the business. âHe did things that could have been done before, but nobody did them,â said Leatherbury with a tone of thankful respect. The bottom line is the health and growth of Maryland racing, under De Francisâ charge, caught the attention of the nation.

De Francis reveled in the success of the Preakness and believed the 1989 event was perhaps the greatest in history from a competitive standpoint as Sunday Silence won by a nose over Easy Goer in an all-out battle through the stretch.

As with any man who is strong-willed and has the courage of his convictions, De Francisâ intensity and his demands created a share of detractors. But he paid them no mind, even moving some of them, including those with ability, out of the way. It was a show he originated, orchestrated and directed.

Now back, briefly, to the letter he never received. It was another lesson that again demonstrates the danger in putting off would-be good intentions until itâs too late, or after-the-fact. De Francis died at age 62 of heart failure and Tuesday some of his friends attended a private, by-invitation-only, memorial service in the chapel at Loyola College in Baltimore conducted by his good friend, the Rev. Joseph Sellinger.

The De Francis era was exciting and took Maryland racing to heights it had never known. He, indeed, was an individual of exceptional talent, a man able to conceive of new ideas and implement them, regardless of cost or inherent problems the procrastinators or opponents placed in front of him.

The final letter, the one he didnât live to read, is expected back at any time. Itâll be marked, regrettably, with the poignant notation: Return To Sender.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.