âFamily Farmâ Tax Break Isnât Chicken Feed

With lobbyists and tax lawyers fidgeting in the wings, the House Ways and Means committee on Tuesday took up reconsideration of last yearâs Tax Reform Act looking to get about $6 billion of new taxes by closing loopholes--among them the curious case of the billion-dollar family farm.

Thatâs a reference to a tax law curiosity that allows farming corporations, no matter how large, to use a method of accounting intended to aid small family farmers. Big companies can qualify as family farms--even if they are listed on major stock exchanges--if 65% of their stock is owned by no more than three families. For example, the company that makes McDonaldâs Chicken McNuggets--Tyson Foods of Springdale, Ark.--qualifies as a family farm even though it has about $1.7 billion in annual sales.

How can that be? Itâs the kind of distortion that arises when tax law makes social policy. Back in 1976, in an earlier change in the tax laws, Congress decreed that all corporations should adopt the same type of cost accounting--called accrual accounting--the type, naturally, that brought the government the most tax money.

Heavy Lobbying

But it exempted family farms, so as not to impose on small businesses the burden of keeping records like big corporations. Farmers could use cash accounting, which allowed them to continually defer taxes by purchasing feed at the end of one tax year and reaping the income from the fattened chicken or animal in the next. As long as they bought the same amount or more feed at the end of each tax year, that is, they could defer taxes indefinitely and thus enjoy an interest-free loan from the government.

A nice deal for those who qualify and, as it happens, 18 of the 20 largest poultry farmers in the United States--names like Perdue, Gold-Kist, Foster Farms, Hudson Foods, Pilgrimâs Pride, Pennfield--are technically family farms and able to use cash accounting, even though all have revenue of $100 million or more and, presumably, are capable of keeping records like any other big company.

So credit the law of unintended consequences for their tax break.

But credit also the law of countervailing power--or more simply, envious competitors--for trying to get it repealed. Among top chicken producers there are two companies whose pattern of stock ownership does not qualify them as family farms. One is ConAgra Inc., an Omaha-based $9-billion (sales) giant of the food industry that is the second-largest chicken producer after Tyson. Holly Farms, a $1.4-billion (sales) Memphis company, is the other chicken producer denied use of the cash accounting tax break. And so Holly and ConAgra are spending money on lobbyists and public relations--$500,000 for a six-month assignment is customary--to persuade Congress to undo the tax break of the big family farmers, who, of course, have hired their own lobbyists to influence Congress to leave the law alone.

Full employment for lawyers and influence peddlers. Is that how the system works?

Gives Competitive Edge

As a matter of fact it is, says Cliff Butler, chief financial officer of Pilgrimâs Pride Corp. of Pittsburg, Tex. That tax benefit, Butler says, âis the reason the consumer enjoys low-priced chickenâ--a reference to the fact that chicken hasnât risen in price in half a century, and can still be had in the supermarket for 60 cents a pound.

But tax breaks arenât the reason. Productivity and economies of scale have made chicken a big and efficient industry. Tyson, for example, has its chickens grown by 6,500 contract farmers and employs 26,000 people itself. ConAgra and the other big producers have similar arrangements. Itâs an industry that will give the American people an estimated 7 billion chickens this year, whether in supermarkets or restaurants.

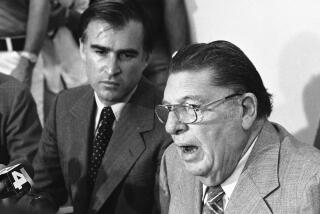

The tax break, in fact, may be a minor thing in such an industry. But it helps, says James Blair, counsel for Tyson Foods, which deferred $100 million in taxes last year. âCash accounting encourages investment,â Blair says. âItâs the way we have always used tax policies, not merely for revenue but for national priorities.â Blair neglects to mention that because it is not available to all, the tax break is a competitive advantage by act of Congress.

It is the kind of thing, in fact, that tax reform was supposed to do away with--distortions arising from the confusion of tax and social policy. The family farm provision survived last year, however, and may indeed survive this week. It is low on Ways and Meansâ list of priorities because repealing it doesnât promise that much additional tax money and the lobbyists for and against it may cancel each other out.

Common sense may say that a billion-dollar business is not a family farm, but lobbyists and tax lawyers have little time for such sentiment.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production â and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.