HOW SAN DIEGO SLIPPED INTO DIFFICULTY

1950s and early 1960s: San Diego and other municipalities discharge sewage--much of it untreated--into San Diego Bay, where the U.S. Navy and post-World War II industries also are dumping toxic wastes. Health officials quarantine both sides of the bay, which ranged in color from bright red to brown.

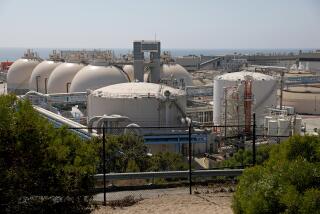

1963: After years of planning, the City and County of San Diego open the Point Loma Wastewater Treatment Plant. The facility uses primary treatment--removing 60% of the suspended solids from the sewage--before discharging sewage into the ocean two miles from shore. Sewage bound for the bay is diverted to Point Loma through a $52-million system of interceptor pipes and pump stations. Soon after Point Loma goes on line, the fouled bay begins to clean itself; marine and plant life reappear.

September, 1970: The city receives an award from the Department of the Interior for cleaning up San Diego Bay by constructing the sewage treatment plant.

1972: Congress passes the Clean Water Act, which mandates that all municipalities dumping sewage into the nationâs waterways upgrade their facilities to include secondary treatment. Advanced treatment removes up to 75% of suspended solids from sewage before it is discharged.

1976: A report by the cityâs consultant recommends that the city fight the move to secondary treatment because primary treatment at Point Loma poses no threats to the ocean environment. The consultant argues that EPA regulations are excessive and necessary only for cities discharging into fresh water sources. Some local scientists assert that sewage is good for the ocean, providing ânutrientsâ for marine life.

1977: Armed with scientific data, San Diego city officials join other coastal cities to lobby Congress for an exemption from EPAâs secondary treatment requirements. Congress agrees, and amends the Clean Water Act to allow for a waiver for municipalities that can prove their sewage discharge does not harm the ocean environment. This move locks San Diego in a decade-long war of wills with the EPA.

1980: The state Water Resources Control Board, the funnel through which federal funds are dispensed to build secondary treatment plants, passes a resolution that says monies will be made available first to cities that discharge their waste into rivers and lakes. San Diego interprets this to mean there will be no money for a proposed South Bay plant, and city officials abandon plans to build the facility. City officials now admit that was a mistake.

March, 1980: A continuous series of sewage spills into Mission Bay forces cancellation of the San Diego Crew Classic, a prestigious, nationally televised event that draws rowing teams from across the country. Tourism officials are horrified about the moveâs effect on San Diegoâs image.

September, 1981: EPA grants the City of San Diego a tentative waiver from secondary treatment standards. The city interprets the decision as final approval and drops all plans for eventual upgrading to secondary treatment--a move some officials now concede was a mistake.

November, 1983: State regulators revise ocean quality standards to protect kelp beds offshore of Point Loma. To comply, the city must extend the underwater sewage outfall by about two miles. Instead of undertaking the $150-million project, city officials decry the new state standards and seek an exemption.

November, 1983: The City of San Diego submits a second, updated waiver application to the EPA.

April, 1985: A massive sewage spill caused by a manhole collapse in Pacific Beach forces the relocation of the San Diego Crew Classic to the eastern portion of Mission Bay. Sail Bay is quarantined.

June, 1986: Staff members of the Regional Water Quality Control Board recommend fining the City of San Diego nearly $1.3 million for sewage system problems. Half of the fine would be for spills from Pump Station 64, a problem-plagued facility that has spewed millions of gallons of raw sewage into Los Penasquitos Lagoon over the past decade. The problems with Pump Station 64 are significant because it handles the sewage from San Diegoâs fastest-growing neighborhoods.

July, 1986: The San Diego City Council enacts a temporary ban on sewage hookups in the Pump Station 64 service area in hopes of convincing state regulators it is serious about fixing the stationâs problems. The ban galvanizes the building industry into urging the city fix Pump Station 64. State regulators fine the city just $11,300 for the Pump Station 64 spills but order San Diego officials to follow a strict schedule of repairs.

September, 1986: EPA tentatively denies the cityâs application for a waiver from secondary treatment requirements.

November, 1986: A Thanksgiving Day spill caused by human error sends 1.5-million gallons of raw sewage into Los Penasquitos Lagoon. Two months later, the state water board fines the city $300,000.

February, 1987: The San Diego City Council votes to relinquish the fight for an EPA waiver and begin planning for an estimated $1.5-billion secondary sewage treatment plant, the single largest public works project in city history. Fearing that growth in the North City would overwhelm Pump Station 64, City Manager John Lockwood imposes a ban on new sewer hookups to the facility until its capacity is expanded with the addition of larger pumps in June, 1988.

March, 1987: Weather-related power surges rupture a force main leading out of Pump Station 64, creating what city officials say is a âdisasterâ by spilling 20-million gallons of raw sewage into Los Penasquitos Lagoon. It is one of the largest sewage spills in the state.

April, 1987: The first sign of what San Diegoâs sewage woes will cost the average citizen is evident. The Water Utilities Department proposes a 63% increase in sewer rates, from $8 to $12.80 a month for the average residential customer. The increase is needed to raise $60 million, $50 million of which would pay for the replacement of deteriorated pipes and for work at Pump Station 64; $10 million is earmarked for consultant fees for upgrading to secondary treatment. Eventually, city officials predict, the monthly bill will total $28.80 to $36.80--a hefty increase needed to pay for the $1.5-billion treatment plant. (The city is too late to receive any federal funding for the project.)

April, 1987: The City Council appoints a citizensâ task force to help San Diego prepare for the $1.5-billion secondary sewage treatment plant. The 22-member group, consisting of representatives from business, the development industry and academia, tackles the politically sensitive task of examining alternatives (like water reclamation) to secondary treatment and looking for a plant site.

May, 1987: State regulators reprimand the city for its record on preventing sewage spills into Mission Bay, all or part of which has been quarantined 27% of the time since 1980. The Regional Water Quality Control Board, finding that 82% of the spills since 1980 were preventable, issues a cease-and-desist order holding San Diego to a schedule for improvements to the aged system of pipes and manholes that ring the bay.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.