Fame Doesn’t Always Make Father Right

- Share via

When he was just a little kid, Sydney Chaplin’s father warned him against taking up golf. “It’s a rich man’s game,” he sniffed.

Which was kind of funny because Sydney’s father was one of the richest men in the world. He left more than $200 million when he died.

His father was also one of the most beloved men in the world. Le Grand Charlot, the French called him, the Great Charlie. The Little Tramp, the rest of the world called him.

As so often happens, Charlie Chaplin was a lot funnier in front of a camera than he was at home. But he was a mammoth artistic talent, probably the greatest the art form that was movies has ever produced.

Reared in the Dickensian poverty that was turn-of-the-century London, where Dad had been a mystery guest and Mom spent years in the poorhouse, little Charlie danced on the street for pennies and tried to duck floggings in the orphanage to which he had been confined. Charlie Chaplin had no trouble conceiving of himself as a penniless, homeless hobo going through life one step ahead of a truant officer or a posse of clumsy cops.

Contentious, licentious, Le Grand Charlot on screen charmed a whole world. He made pictures that stand up as art to this day and were to movies what Rembrandts were to oils.

Married four times, he had two sons by his second wife, Lita Grey, the ingenue actress. Sydney was one of them, named for Charlie’s beloved older brother, the one who had rescued him from street corner pantomimes and put him on a boat to America.

The movies made Chaplin but Chaplin also made the movies. He earned a million dollars a year in the days when you could keep most, if not all of it, and he lived in the most incredible luxury.

But he saw himself as society’s victim, son Sydney says, and he never escaped the psychological scarring of his childhood.

He ended up being knighted but was banned for years from his adopted America for patent pro-Soviet views. His son notes, however, that Charlie Chaplin was no Bolshevik, just a product of gaslight England where the poor starved and the rich hunted foxes.

So, it was with great interest that I noted an item the other day saying that the son of Charlie Chaplin had won a golf tournament in Hawaii. Sydney Chaplin was low celebrity in the Aku Cup tournament, Danny Arnold’s annual celebrity bash on the island of Maui, where it is known as “the Crosby of the Islands.”

Sons and daughters of the late Charlie Chaplin are not rare in nature--he had 10 children by Oona O’Neill--but those were late-life children brought up in Swiss chalets. Sydney lived through the glory years, the golden ‘20s, when Hollywood was Hollywood.

How many people do you know who played tennis with Garbo, held the pages for Albert Einstein to play the fiddle, shared a bachelor pad with Gene Kelly, was a guest at San Simeon when William Randolph Hearst was alive?

What was it like to go through life as “Charlie Chaplin’s son” in the days when father was not a star on a sidewalk or a musty page in a book but a legend in his own time?

“Well,” allows Sydney Chaplin--his late brother was Charles Chaplin Jr.--”I went to Black Fox Military Academy, where Buster Keaton’s son went, Bing Crosby’s sons went and you thought nothing of it, like ‘Isn’t everybody Charlie Chaplin’s son?’ ”

Dad might have been a laugh a minute on screen but he was a driven man, his son recalls, what would now be called a workaholic. His son remembers that he could never put away his Oliver Twist beginnings, no matter how many Rolls-Royces were parked in the driveway of the Beverly Hills mansion.

“Even when he was sitting up there in his Swiss castle with 10 servants and numbered bank accounts, he would get the meat bill and be appalled and say ‘OK, everybody goes on a vegetable diet,’ until he wanted his lamb chops again a day or two later.”

Unlike many of the sons of the rich, Sydney did not rebel against his heritage. “Hell,” he says, “it helped.”

He became a Broadway star--”Bells Are Ringing,” “Subways Are for Sleeping”--but he has less success in Hollywood.

“I played Indians,” he says. “I sat around in the commissary in pigtails and said ‘Ugh!’ on camera.”

He does fault his father for one thing. For keeping him from the joys of golf, if joys is the word.

“For 25 years, I passed up golf for tennis,” Chaplin says. “He convinced me golf was for old, rich men--he who had Bill Tilden as his tennis instructor!

“But you know something? I can’t recall a single shot I ever made in tennis--but I can tell you ever birdie I ever made in golf!”

Now a restaurateur in Palm Springs--Chaplin’s, on Frank Sinatra Drive--Sydney Chaplin is neither old nor rich, he says. But he is hooked on golf.

His victory in the Aku tournament outranks even the Tony he won on Broadway for “Bells Are Ringing,” he says. Gloats the son of the great Charlot , “I sank a 100-foot putt. Nicklaus would have been glad to get within 10 feet of the hole!”

He gets invited to the Aku tournament because of his long friendship with the tournament’s sponsor and angel, Danny Arnold, creator of the TV show, Barney Miller.

“The star of the show, Hal Linden, was my understudy in ‘Bells Are Ringing,’ ” he notes. “How’s that for small world?”

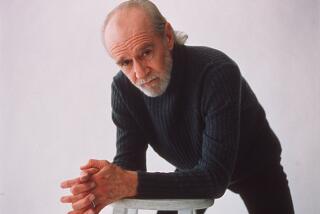

He gets invited also because he’s the son of perhaps the most famous movie star in history. Now 61, he has no adversary memory of his famous father. “To this day, I think ‘City Lights’ is the greatest single motion picture ever made,” he says.

If his father failed him, it was in steering him off golf all those years. “Just think,” he jokes, “I coulda won the British Open!”

The big three could have been Nicklaus, Palmer and Sydney Chaplin.

For now, he makes do with his 20 handicap. But he can play to it. Even though people half-expect him to come out in a battered derby hat and shoes two sizes too large and begin hitting the ball with this skinny cane while being chased by a whole bunch of cross-eyed cops in helmets.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.