Independent Counsel Gets Powers, Protections It Needs

When Atty. Gen. Edwin Meese III announced his intention to ask a special panel of federal circuit court judges to appoint an independent counsel to investigate the Iran- contra affair, reporters peppered him with questions about the role of this âspecial prosecutor.â

Meese corrected them, insisting that âthereâs no such thing as a special prosecutor. Itâs an independent counsel.â

Indeed, some things besides the name have changed since the term âspecial prosecutorâ became part of the nationâs legacy of Watergate.

For one thing, the office has become institutionalized by Congress--first in 1978 and again in 1983. Amendments made in â83 give the attorney general greater discretion in deciding when to conduct a preliminary investigation and when to request appointment of an independent officer to continue that investigation.

Moreover, the new version of the law now makes it clear that the independent officer can dismiss a matter without actual investigation, and can provide for court-approved reimbursement of expenses incurred by those who are investigated and exonerated. These changes were the result of lessons learned during the investigation of Hamilton Jordan, chief of staffin the Carter Administration. Although the special prosecutor in Jordanâs case believed initially that there were no substantive grounds for prosecution, an investigation was nevertheless conducted that left Jordan with legal fees of more than $100,000.

But one thing hasnât changed--the power of the independent counsel. Suggestions in the press that parallel investigations by Congress and by an independent counsel might somehow interfere with each other are unfounded.

The Constitution charges the President with the task of faithfully executing the laws of the land, and the Supreme Court has noted that it is the role of the attorney general to act as âthe hand of the Presidentâ in carrying out that high responsibility. The conflict of interest inherentin investigating oneâs peers or superiors makes it impossible for an attorney general or any Administration official to function independently.

In a situation like this the nation will have faith only in a careful investigation and a thorough report by a government outsider. To succeed, the independent counsel must have the power to conduct an effective investigation and must be insulated from political pressures. The law provides both.

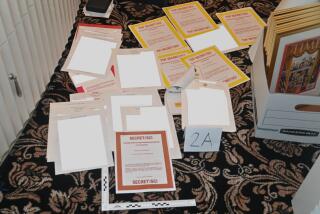

The independent counsel will have âindependent authority to exercise all investigative and prosecutorial functions and powersâ of the attorney general and the Department of Justice. These include wide-ranging powers such as the right to national-security clearances and the right to contest any claim of privilege or attempt to withhold evidence on the grounds of national security. Such powers will be indispensable to the investigation of a matter that the Justice Department has characterized as requiring an appreciation of âinternational relations, national security and defense, intelligence, counterterrorism, foreign aid and foreign military sales, as well as familiarity with the manner of execution of American foreign policy.â

Most important, the independent counsel will be protected from dismissal. The attorney general can fire an independent counsel only for âgood cause,â physical disability or mental incapacity, and must specify the reasons for dismissal in a report to the special panel of judges and both the House and Senate Judiciary committees. If the dismissal is unwarranted, the special panel of judges can reinstate the independent counsel. Although the âgood causeâ standard represents a retreat from the âextraordinary improprietyâ standard of the original version of the law, it provides a measure of protection that should prevent another Watergate-style âSaturday Night Massacre.â

That protection is especially important in light of this Administrationâs distaste for the special-prosecutor law. In the early days of the Reagan era the Justice Department, citing doubts about the constitutionality of the law, even went so far as to call for its repeal.

This latest scandal should also serve to remind both Congress and the public of the wisdom of a law that provides for the appointment of independent investigators, whatever their title. As Congress begins its own investigation of the Iran-contra matter, it should also consider extending the special-prosecutor/independent-counsel law beyond its new scheduled expiration date of Jan. 3, 1988.

Clearly, the need of Congress and the public to learn what happened in this current extraordinary affair and the need for a thorough, deliberate and totally independent investigation of possible violations of federal law by high-level government officials are both essential to a functioning democracy.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.