PACOâS STORY <i> by Larry Heinemann (Farrar, Straus & Giroux: $15.95; 191 pp.)</i>

The most profound social distinction is the one between the living and the dead. Ghosts have fallen into the lower classes. They are as invisible as Ralph Ellisonâs Invisible Man, as the Hispanic busboy in a high-priced restaurant, or as the Suffolk laborers in âAkenfieldâ who patterned their work schedules so that estate owners would not be troubled by the sight of them.

Like others who have written fiction about the Vietnam War in recent years, Larry Heinemann is haunted by its present invisibility only a dozen years after it ended. Hundreds of thousands of veterans, tens of thousands of them dead, fall under that dark American shadow: to be out of fashion, not hot, off of prime time.

âPacoâs Story,â brief and with a remarkable intensity, presses the social claims of those who died literally, and those who survived but whose history, for all the place it has today, might as well be dead. Using the simplest of stories--a grievously wounded veteran gets off a bus in a small Texas town, finds work, stays a while and moves on--Heinemann writes of the two universes that coexist in our country: the large one that canât remember, the small one that canât forget.

Heinemann foreshortens the remembering and forgetting. Paco Sullivanâs brief passage through Boone, Tex., takes place not now but while the fighting was still going on, or perhaps recently over.

Even then, the line between those who are at peace and those who are at war is brutally drawn.

Pacoâs Spanish name and Irish surname make no special point except to declare him a kind of unprivileged Everyman. He is the sole survivor of Alpha Company. It was destroyed, in a single moment, by a barrage of âsupportingâ fire while defending its outpost against a Viet Cong attack.

And Paco himself was so badly hurt that the word survivor scarcely applies. That is the bookâs theme. It is also the inspired device that makes Pacoâs encounters such a glowing metaphor for this theme.

Heinemann puts the narration of Pacoâs sojourn in Boone in the mouths of his dead companions. âPacoâs Storyâ seems to be told by ghosts. I donât think the author means these ghosts literally, although this is purposely ambiguous.

More likely, Paco feels himself to be one of the dead as well, and tells his story on their behalf. He speaks of himself in the third person, as if the living Paco were an accidental surviving limb of his own essentially dead self. It is the way you might speak of an amputated appendix. Not âI was removed,â but âMy appendix was removed.â

The horror that Heinemann wants to rescue from oblivion is expressed in the notion that it is not death that amputates the victim from the survivor, but life that has amputated the survivor from the company of the dead.

The ghostly voice, which by turns is colloquial, brutal, obscene and remarkably cheerful, and which, throughout the book, addresses an imaginary listener named James--I havenât the slightest idea who he is--begins by assuming that most people wonât want to hear its story. It is aware of its own low social standing.

Then it goes on to relate tersely and vividly the ordinary hell of Alpha Companyâs existence, and the special hell of its destruction. It tells of the discovery of Pacoâs shattered body among the minute fragments of his companionsâ corpses; and of his slow and painful mending in a hospital. It is a recovery as precarious and unlikely as Lazarusâ.

The narration moves forward to tell of Paco arriving in Boone--simply a matter of giving all his money to the bus driver to go as far as it was good for--and of his time there. Continually, it reverts to the war days. It is as if only the terrible past were believable, and as if the everyday life in Boone were an invention too fantastic to sustain.

Paco, crisscrossed with scars, limping and in continual pain, goes from door to door looking for a job. It is a stunning chain of vignettes. He visits an antique shop whose owner, a refugee from the concentration camps, hallucinates that he is his dead son; and to a barbershop where the townspeople look at him as if he were from another planet. Finally, the owner of the local diner, a World War II veteran, hires him as a dishwasher and, without listening to Pacoâs story, tells him his own story about the bloody days in the Pacific.

Paco tries to hold on to this life, as strange to him as a grafted organ. (Heinemann conveys the effort with a minute description, lasting an audacious and oddly gripping six pages, of just how Paco gathers up, washes and replaces the dinerâs dishes and pans.) But the graft doesnât take.

Paco, and the larger phenomenon he represents, is not real to the townspeople; they are not real to him. They are two entirely different aquatic species, swimming side by side in the same aquarium.

He is attracted to a young woman who lives next door in his broken-down hotel; and she is aroused by him and his scars. But on her side, it is a peripheral fantasy she indulges in while making noisy love with her boyfriend. Paco listens sleeplessly to the lovemaking and is seized by desire. But desire leads him away, and back to the real world of memory. It is a memory, told in dreadful detail, of the rape-killing by Alpha Company of a Viet Cong woman prisoner.

Pacoâs young neighbor comes close to him only in a dream. She dreams of making love, in the course of which she peels off his hundreds of scars and lays them gently upon her. The image could be grotesque; but it is delicate and heartbreaking.

Dreams are the closest we come, Heinemann is saying in his deeply original and affecting book, to bridging the gulf between our lives and our snubbed, dead history.

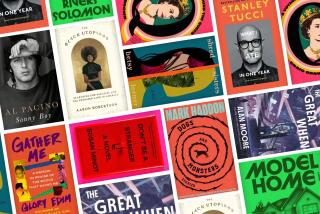

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.