A New Direction for Feminism : Equality Is Giving Way to Working Womenâs Special Needs

Whatâs happening to the feminist movement? It seems to have come to a standstill, and there is reason to think that when it gains momentum again it may be moving in a new direction.

The leaders of the National Organization for Women marked their 20th anniversary this summer by bickering about their future agenda, while critics charge that the American feminist movement has become unresponsive to the real needs of American women.

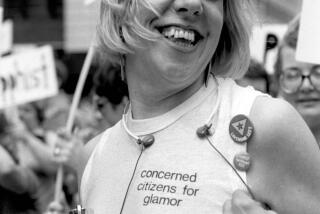

In the early 1960s domesticity came under attack from women like Betty Friedan, whose âThe Feminine Mystiqueâ spoke to the discontents of well-educated and well-to-do women to whom careers outside the home held out the promise of glamour, independence and equality with men. The machinery for change was already in place. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 had included a provision against job discrimination on the basis of sex as well as race. Activists like Friedan saw the opportunity and the National Organization for Women was founded to pressure the courts and the legislatures to enforce the anti-sex-bias laws and support an equal rights amendment.

At the same time younger women, college-student activists, were protesting their second-class status in the male-dominated civil-rights and campus anti-war movements, and when they broke away to form âconsciousness-raisingâ groups the womenâs-liberation movement was born.

By 1970 American society had changed drastically, with more women entering graduate and professional schools, with more electing to go to work first and to marry and have children later, and with nearly half of all married women--and more than half of all mothers of school-age children--at work outside the home.

In 1972 the ERA was finally approved by Congress. The victory climaxed a decade of legal and social change, and the following year saw state anti-abortion laws struck down by the U.S. Supreme Courtâs Roe vs. Wade decision.

It seemed that nothing could stop the feminist steamroller. Somewhere along the way, however, the womenâs movement had lost touch with the real concerns of most women, who had continued to marry and have children and to whom the anti-male and sexually egalitarian philosophy of the feminists seemed irrelevant. It was women who defeated the ERA.

By the early 1980s it was apparent that the feminist agenda had served many women badly. Liberalized divorce laws bought legal equity at the price of traditional legal protections, and often left women and their children worse off than their former husbands.

Today more than 8 million mothers of preschool children and half of all women with children under 3 are out at work--the fastest growing segment of the work force.

While women have overtaken men in many job markets, they have failed to catch up to them in earnings. And many working women feel as trapped in their jobs as they once felt trapped at home. In fact, they seem to be in a double bind, with often-conflicting responsibilities on the job and, after working hours, at home.

Even feminists seem disenchanted with the way things have worked out. Taking stock, they have been calling for a reappraisal of priorities. Many, like Friedan, have come out in favor of a shift of emphasis from legislative issues of equity to family issues, recognizing that abortion rights and the ERA are less central concerns of American women today than child-care programs and job leaves for parents of newborns and sick children. In the womenâs-issue book of the moment, economist Sylvia Ann Hewlett argues that American women lag far behind their counterparts in Western European countries like Britain and socialist Sweden in such workplace benefits as maternity leave and subsidized child-care facilities.

If the response to Hewlettâs âA Lesser Lifeâ is any indication, the womenâs movement is taking a new direction--a long way from where it all began with âThe Feminine Mystiqueâsâ exhortation to compete in a manâs world. Having done so, women seem to be in the work force to stay, and, for better or for worse, that includes mothers.

The future of the movement may lie in efforts to resolve the conflict between work and family. Demands for family support systems will most likely focus not only on employment benefits like maternity and paternity leave, flexible schedules and on-site day-care facilities, but also on such tax measures as increasing the personal exemption and earned-income credits for parents. There are even those who, questioning the long-term effects of two working parents and group child-rearing arrangements, suggest extending existing child-care expense deductions for working mothers to mothers who stay home.

Ironically, 20 years of feminist progress seems to have gotten women out of the home only to create new problems for them. And the solutions being offered bring us back full circle to the pre-World War II approach of protective legislation for women and children. The new direction for feminism seems to be away from a demand for equality to a recognition of the need for special treatment.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.