Major Leagues Train Eyes on Jordan’s White After 20-K Gem

LONG BEACH — One brilliant game, so sweet it seemed like a dream that should never be awakened from, has made him a phenomenon of spring.

And now the major league scouts, carrying radar guns so they can time his fastball, arrive in flocks--”The head guy from Milwaukee is flying in, the head guy from the Braves is flying in,” the phenom’s coach says excitedly.

And the girls in the corridors of Jordan High School are taking notice too, so much that when Fred White stepped onto the diamond Monday, he had lipstick on his cheek.

“Who kissed you?” asked Jordan Coach Bill Powell at Houghton Park, where palm trees loomed like skyscrapers above the baseball field where Jordan practices.

“A girl at school, she hadn’t seen me in a week,” said White, smiling sheepishly as he prepared to loosen up the pitching arm which on March 14 struck out 20 Lakewood High batters in nine innings at Blair Field.

Shades of the ‘Big Train’

It was such an astounding total that suddenly White found himself being mentioned with Hall of Famer Walter (Big Train) Johnson, who set the California high school strikeout record of 27 in 1905 when he pitched for Fullerton.

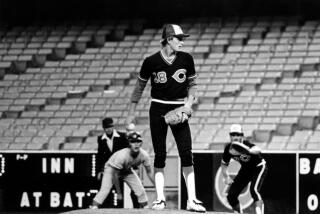

Tall, strong and supple, White took the pitching mound and began practice.

He wound up in a rapid motion, kicked out his left leg and fired. His pitches came in low and arrived at home plate with a big train’s momentum in a terrifying instant. Some popped from the mitt of the catcher, Robert Sanderson, who said, “I’d be scared to bat against him.”

And the right-hander didn’t even show his curve ball, a pitch that he has the confidence to throw in the most crucial situations. Against Lakewood he got some of his strikeouts by throwing the curve with a count of three balls and two strikes. Rare is the high-school pitcher who can do that.

“I wasn’t really thinking about how many strikeouts I had,” White said of his big game. “I just wanted to win. It was very sad that we lost (3-2) because the game meant a lot to the team. I want to do something for Jordan. The school’s been down so long, everybody thinks we’re going to lose.” (The Panthers haven’t been to the playoffs in 10 years).

White, a 17-year-old senior, has struck out 60 batters in 38 innings this season and has walked only 15. In his first five games he allowed just seven runs. But Tuesday night against Poly, White gave up nine unearned runs and lost, 9-4. He started the game with three strikeouts, and led, 3-1, after five innings. But Poly, helped by errors, scored eight runs in the sixth inning to drop White’s record to 2-2.

His overall statistics are so sparkling that scouts, hopeful of discovering another Dwight Gooden--the star pitcher of the New York Mets whom White idolizes and resembles physically--call Powell daily and ask when White will pitch again.

In his next start after the Lakewood game, more than a dozen scouts sat in the dimly lit grandstand behind the backstop at Blair Field as he beat Millikan, 8-1. He pitched a six-hitter but had only seven strikeouts. Neither he nor Powell were satisfied with that effort.

“I was nervous,” White said. “I saw all the scouts.”

The scouts, though, were impressed.

“He’s just a good athlete,” Don Lindeberg said that night as he jotted notes in a little black book. “It’s the fifth inning and he’s not losing anything.”

Lindeberg, 71, of Anaheim, a longtime scout for the New York Yankees, assessed White: “He knows how to pitch. His fastball is 84-85 miles per hour, which is the big-league average, and it moves. And he’s got a great body (6 feet 2, 180 pounds) for a pitcher. I would say he’s got a chance to be a high draft choice.”

White’s emergence as a top prospect has been somewhat sudden, even though he had a city-leading 0.64 earned run average last season.

“His stock has really gone up,” Powell said. “He throws harder than he did last year, has a lot better control and his composure has improved. He expects to win when he goes to the mound. If he gets a (professional) pitching coach to teach him the right mechanics (after high school), his potential is unlimited.”

But Powell stressed that one great game does not ensure a ticket for White to professional baseball.

“He’ll have to come up with another game like Lakewood to keep his credentials,” Powell said.

White is determined to do that, for the desire to make the big leagues has long burned within him.

He was born in St. Louis, but when he was 5 his family moved to Carson, where he first dreamed of being a major leaguer. But he lived in a neighborhood where reality made dreaming foolish at best.

“The guys would say, ‘You’ll never stick to baseball, you’ll be a bad guy.’ ” White said. “But I was never the type to steal anything.”

His friends were, however. “Most of them are in jail,” White said.

After about six years in Carson, White moved to North Long Beach, where he now lives, near Jordan with his mother, Barbara Upshaw, and his stepfather, Robert Upshaw.

It is an area where trouble can be around the next corner, but White--as he did in Carson--avoids it.

“A lot of guys would like to fight me because I’m popular,” White said. “They probably think I’m bigheaded, but I’m not. I hate to back down but I can’t see fighting someone and messing up my career.”

It was on the advice of his Little League coach, Ike Childress, that White chose a straight and narrow path.

When White was 11, he hit a home run over the fence at Coolidge Park in North Long Beach. The ball landed on the Artesia Freeway, a drive that so impressed Childress that he nicknamed White “Freeway Freddie” and told him that if he hung in there and stayed out of trouble, he’d go a long way in baseball.

“He died about a month ago,” White said of Childress. “That really hurt me.”

The smile above the thin mustache disappeared, but the thought of going a long way in baseball brought it back quickly.

That thought obsesses him.

“(Sometimes) I’ll black everything out and think about baseball as a career,” he said. “That’s what I want it to be. I want to die playing baseball.”

Recently, White received a call from a Chicago Cubs scout, the first time he had ever talked to a scout. It took him straight to heaven. He lay down that night about 8 and “dreamed I was playing in the big leagues with Dwight Gooden and that I bought my mom a nice home.”

It was almost too delicious to comprehend, just like the night against Lakewood. He didn’t want to wake up.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.